09.12.2025 à 15:17

‘We need to rethink how we approach biodiversity’: an interview with IPCC ecologist and ‘refugee scientist’ Camille Parmesan

Texte intégral (6222 mots)

She is an ecologist recognized worldwide for being the first to unequivocally demonstrate the impact of climate change on a wild species: the Edith’s checkerspot butterfly. In recent years, however, Camille Parmesan has been interviewed not only for her expertise on the future of biodiversity in a warming world or for her share in the Nobel Prize awarded to the IPCC, but for her status as a refugee scientist.

Twice in her life, she has chosen to move to another country in order to continue working under political conditions that support research on climate change. She left Trump’s America in 2016, and later post-Brexit Britain. She now lives in Moulis in the Ariège region of southwestern France, where she heads the CNRS’s Theoretical and Experimental Ecology Station.

Speaking with her offers deeper insight into how to protect biodiversity – whose responses to climate change continue to surprise scientists – what to do about species that are increasingly hybridizing, and how to pursue research on a planet that is becoming ever more climate-skeptical.

The Conversation: Your early work on the habitats of the Edith’s checkerspot butterfly quickly brought you international recognition. In practical terms, how did you demonstrate that a butterfly can be affected by climate change? What tools did you use?

Camille Parmesan: A pickup truck, a tent, and a butterfly net, good strong reading glasses to search for very tiny eggs and caterpillar damage to leaves, a notebook and a pencil to write notes in! In the field, you don’t need more than that. But before doing my fieldwork, I had spent a year going around museums all across the USA, a couple in Canada, and even in London and Paris collecting all the records for Edith’s checkerspot. I was looking for really precise location information like ‘it was at this spot, one mile down Parsons Road, on June the 19th, 1952’, because this species lives in tiny populations and is sedentary. That process alone took about a year, since at the time there were no digitized records and I had to look at pinned specimens and write their collecting information down by hand.

Once in the field, my work consisted of visiting each of these sites during the butterfly’s flight season. Since the season lasts only about a month, you have to estimate when they will be flying in each location in order to run a proper census. For this, you start by looking for adults. If you do not see adults, you do not stop there. You look for eggs, evidence of web, like bits of silks, damage from the overwintering larvae starting to feed…

You also look at the habitat: does it have a good quantity of healthy host plants? A good quantity of healthy nectar plants for adult food? If the habitat was not good, that location did not go into my study. Because I wanted to isolate the impact of climate change, from other factors like habitat degradation, pollution… At the larger sites, I often searched more than 900 plants before I felt like I had censused enough.

Today, when you go back to the fields you started monitoring decades ago, do you see things you were not able to see at the beginning of your work?

C. P.: I know to look for things I didn’t really look for when I started 40 years ago, or that my husband Michael [the biologist Michael Singer] didn’t look for when he started 50 years ago. For instance, we discovered that the height at which the eggs are laid is a bit higher now, and that turns out to be a really significant adaptation to climate change.

The eggs are being laid higher because the ground is getting far too hot. Last summer, we measured temperatures of 78°C (172.4°F) on the ground. So if a caterpillar falls, it dies. You can also see butterflies landing and immediately flying up, as it is way too hot for their feet and they’ll then fly onto vegetation or land on you.

In my early days, it wouldn’t have occurred to me that the height of where the eggs are laid could be important. That is why it is so important for biologists to simply watch their study organism, their habitat, to really pay attention. I see a lot of young biologists today who want to run in, grab a bunch of whatever their organism is, take it back to the lab, grind it up and do genetics or look at it in the lab. That’s fine, but if you don’t spend time watching your organism and its habitat, you can’t relate all your lab results back to what is actually happening in the wild.

Thanks to your work and that of your colleagues, we now know that living organisms are greatly affected by climate change and that many species must shift their range in order to survive. But we also know that it can be difficult to predict where they will be able to persist in the future. So what can be done to protect them? Where should we be protecting lands for them?

C. P.: That is the big question plaguing conservation biologists. If you go to the conservation biology meetings, a lot of people are getting depression because they don’t know what to do. We actually need to change the way we think of conservation, away from strict protection toward something more like a good insurance portfolio. We don’t know the future, therefore we need to develop a very flexible plan, one that we can adjust as we observe what’s happening on the ground. In other words, don’t lock yourself into one plan, Start instead with an array of approaches, because you don’t know which one will work.

We just published a paper on adapting, for land conservation, some decision-making approaches that have been around since the 1960s in fields known to be unpredictable, like economics, for instance, or urban water policy, where you don’t know in advance if it is going to be a wet year or a dry year. So urban planners came up with these approaches for dealing with uncertainty.

With modern computers, you can simulate 1000 futures and ask: if we take this action, what is happening? And you see it is good in these futures, but bad in those, and not too bad in others. What you’re looking for is a set of actions that is what they call robust – that performs well across the largest number of futures. For conservation, we did so by starting with standard bioclimatic models. We had about 700 futures for 22 species. It turns out that if we just protect where these species occur today, most organisms don’t survive. Only 1 or 2% of the futures actually contain those species in the same place. But what if you protect where it is now, but also where it’s expected to be 30% of the time, 50% of the time, 70% and so on? You have these different thresholds. And from these different future possibilities, we can determine, for instance, that if we protect this location and that one, we can cover 50% of areas where the models predict the organism persists in the future. By doing that, you can see that some actions are actually pretty robust, and they include combinations of traditional conservation, plus protecting new areas outside of where the species are now. Protecting where it is now is usually a good thing, but it is often not enough.

Another thing to bear in mind is that bigger is better. We do still need to protect lands for sure, and the bigger the better, especially in high biodiversity areas. You still want to protect those places, because species will be moving out, but also moving in. The area might end up with a completely different set of species than it has today, yet still remain a biodiversity hotspot, perhaps because it has a lot of mountains and valleys, and a diversity of microclimates.

On a global scale, we need to have 30 to 50 percent of land and ocean as relatively natural habitat, without necessarily requiring strict protection.

Between these areas we also need corridors to allow organisms to move without being killed immediately. If you have a bunch of crop land, wheat fields for example, anything trying to move through them is likely to die. So you need to develop seminatural habitats winding through these areas. If you have a river going through, a really good way to do this is just have a big buffer zone on either side of the river so that organisms can move though. It doesn’t have to be a perfect habitat for any particular organism, it just has to not kill them. Another point to highlight is that the public often doesn’t realize their own backyards can serve as corridors. If you have a reasonably sized garden, leave part of it unmown, with weeds. The nettles and the bramble are actually important corridors for a lot of animals. This can be done also on the side of roads.

Some incentives could encourage this. For example, giving people tax breaks for leaving certain private areas undeveloped. There are just all kinds of ways of thinking about it once you shift your mindset. But for scientists, the important shift is to not put all your eggs in one basket. You cannot just protect where it is now, or just pick one spot where you think an organism is going because your favorite model says so, or the guy down the corridor from you uses this model. At the same time, you cannot save everywhere a species might be in the future, it would be too expensive and impractical. Instead, you need to develop a portfolio of sites that is as robust as possible, given financial constraints and available partnerships, to make sure we won’t completely lose this organism. Then, when we stabilize the climate and eventually bring it back down, it’s got the habitat to recolonize and become happy and healthy and whole again.

Another issue that is very much on the minds of those involved in biodiversity protection today is hybridization. How do you view this phenomenon, which is becoming increasingly common?

C. P.: Species are moving around in ways they haven’t done in many thousands of years. As they are moving around, they keep bumping into each other. For example, polar bears are forced out of their habitat because the sea ice is melting. It forces them to be in contact with brown bears, grizzly bears, and so they mate. Once in a while, it’s a fertile mating, and you get a hybrid.

Historically, conservation biologists did not want hybridization, they wanted to protect the differences between species, the distinct behavior, look, diet, genetics… They wanted to preserve that diversity. Also, hybrids usually don’t do as well as the original two species, you get this depression of their fitness. So people tried to keep species separate, and were sometimes motivated to kill the hybrids to do so.

But climate change is challenging all of that. The species are running into each other all the time, so it is a losing battle. Also, we need to rethink how we approach biodiversity. Historically, conserving biodiversity meant protecting every species, and variety. But I believe we need to think more broadly: the goal should be to conserve a wide variety of genes.

Because when a population has strong genetic variation, it can evolve and adapt to an incredibly rapidly changing environment. If we fight hybridization, we may actually reduce the ability of species to evolve with climate change. To maintain high diversity after climate change – if that day ever comes – we need to retain as many genes as possible, in whatever form they exist. That may mean losing what we perceive as being a unique species, but if those genes are still there, it can revolve fairly rapidly, and that’s what we’ve seen with polar bears and grizzly bears.

In past warm periods, these species came into contact and hybridized. In the fossil record, polar bears disappear during certain periods, which suggests there were very few of them at the time. But then, when it got cold again, polar bears reappeared much faster than you’d expect if they were evolving from nothing. They likely evolved from genes that persisted in grizzly bears. We have evidence that this works and it is incredibly important.

Something that can be hard for non-scientists to understand is that, on the one hand we see remarkable examples of adaptation and evolution in nature (for instance trees changing the chemistry of their leaves in response to herbivores, or butterflies changing colors with altitude… ) while, on the other hand, we are experiencing massive biodiversity loss worldwide. Biodiversity seems incredibly adaptable, but is still collapsing. These two realities are sometimes hard to connect. How would you explain this to a non-specialist?

C. P.: Part of the reason is that ongoing climate change is happening very quickly. Another reason is that species have a pretty fixed physiological niche that they can live in. It is what we call a climate space, a particular mix of rainfall, humidity and dryness. There is some variation, but when you get to the edge of that space, the organism dies. We don’t really know why that is such a hard boundary.

When species face other types of changes like copper pollution, light and noise pollution, many of them have some genetic variation to adapt. That doesn’t mean these changes won’t harm them, but some species are able to adjust. For example, in urban environments today, we see house sparrows and pigeons that have managed to adapt.

So there are some things that humans are doing that species can adapt to, but not all. Facing climate change, most organisms don’t have existing genetic variation that would allow them to survive. The only thing that can bring in new variation to adapt to a new climate is either hybridizing – which will bring in new genes – or mutations, which is a very slow process. In 1-2 million years, today’s species would eventually evolve to deal with whatever climate we’re going into.

If you look back hundreds of thousands of years when you had the Pleistocene glaciations, when global temperatures changed by 10 to 12°C, what we saw is species moving. You didn’t see them staying in place and evolving.

Going back even further to the Eocene, the shifts were even bigger, with enormously higher CO2 and enormously warmer temperatures, species went extinct. As they can’t shift far enough, they die off. So that tells you that evolution to climate change is not something you expect on the time scale of a few 100 years. It’s on the time scale of hundreds of thousands to a couple of million years.

In one of your publications, you write: “Populations that appear to be at high risk from climate change may nonetheless resist extinction, making it worthwhile to continue to protect them, reduce other stressors and monitor for adaptive responses.” Can you give an example of this?

C. P.: Sure, let me talk about the Edith’s checkerspot, as that’s what I know the best. Edith’s checkerspot has several really distinctive subspecies that are genetically quite different from each other, with distinct behaviors, and host plants. One subspecies in southern California has been isolated long enough from the others that it is quite a genetic outlier. It’s called the Quino checkerspot.

It is a subspecies at the southern part of the range, and it’s being really slammed by climate change. It already has lost a lot of populations due to warming and drying. Its tiny host plant just dries up too fast. It’s lost a lot due to urbanization too: San Diego and Los Angeles have just wiped out most of its habitat. So you might say, well, give up on it, right?

My husband and I were on the conservation habitat planning for the Quino Checkerspot in the early 2000s. By that time, about 70% of its population had gone extinct.

My husband and I argued that climate change is going to slam them if we only protected the areas where they currently existed, because they were low elevation sites. But we thought, what about protecting sites, such as at higher elevations, where they don’t exist now?

There were potential host plants at higher elevation. They were different species that looked completely different, but in other areas Edith’s checkerspot used similar species. We brought some low elevation butterflies to this new host plant, and the butterflies liked it. That showed us that no evolution was needed. It just needed the Quino checkerspot to get up that high, and it would eat this, it could survive.

Therefore, we needed to protect the area where they were at the time, for them to be able to migrate, as well as this novel, higher habitat.

That’s what was done. Luckily, the higher area was owned by US Forest Service and Native American tribal lands. These tribes were really happy to be part of a conservation plan.

In the original area, a vernal pool was also restored. Vernal pools are little depressions in the grounds that are clay at the bottom. They fill up with water in the winter and entire ecosystems develop. Plants come up from seeds that were in the dry, baked dirt. You also get fairy shrimp and all kinds of little aquatic animals. The host plant of the Quino checkerspot pops out at the edge of the vernal pool. It is a very special habitat that dries up around April. By that time, the Quino checkerspot has gone through its whole life cycle, and it’s now asleep. All the seeds have dropped and are also dormant. The cycle then starts again the next November.

Sadly, San Diego’s been bulldozing all the vernal pools to create houses and condos. So in order to protect the Quino checkerspot, the Endangered fish and wildlife service restored a vernal pool on a small piece of land that had been full of trash and all-terrain vehicles. They carefully dug out a shallow depression, lined it with clay and planted vegetation to get it going. Among other things, they planted Plantago erecta, which Quino checkerspot lives off.

Within three years, this restored land had almost all of the endangered species it was designed for. Most of them had not been brought in. They just colonized this new pool, including Quino checkerspot.

After that, some Quino checkerspot were also found in the higher-environment habitat. I was blown away to be honest. We didn’t know this butterfly would be able to get up the mountain. I thought we’d have to pick up eggs and move them. The distances aren’t large (a few kilometers over, or 200 m upward), but remember that this butterfly doesn’t normally move much – it mostly stays where it was born.

Was there a wildlife corridor between these two areas?

C. P.: There were some houses, but they were very sparse, with lots of natural scrubby stuff in between. There weren’t really host plants for the Quino checkerspots. But it would allow them to fly through, have wild nectar plants on the way and not be killed. That’s the big point. A corridor doesn’t have to support a population. It just has to not kill it.

You too have had to relocate during your career in order to continue your research in ecology without being affected by the political climate. Over the past year in France, you have been asked to speak about this on numerous occasions and have been the subject of many articles describing you as a scientific refugee. In the United States, does this background also generate curiosity and media interest?

C. P.: A lot of colleagues, but also just people I know and have not necessarily collaborated with have asked me: How did you do that? How hard is it to get a visa? Do people speak English in France? But what’s interesting is the media in the USA has taken no interest. The media attention has been entirely outside of the USA, in Canada and Europe.

I don’t think Americans understand how much damage is being done to academia, education and research. I mean, even my own family doesn’t understand how much harm is being done. It’s difficult to explain to them because several of them are Trump supporters, but you would think the media would talk about that.

Most of the media have articles about damage to the university structure and damage to education, banning of books for instance, or the attempt to have an education system that only teaches what JD Vance wants people to learn. But you don’t really have a lot in those articles about people leaving. I think Americans can sometimes be very arrogant. They just presume America is the best and that no one would leave America to work somewhere else.

And it’s true that the USA traditionally has had such amazing opportunities, with so much funding from all kinds: many governmental agencies, funding many different projects, but also private donors, NGOs… All of this really literally stopped just cold.

In order to get people interested in biodiversity conservation and move them out of denial, it can be tempting to highlight certain topics, such as the impact on human health. This is a topic you have already worked on. Does it resonate more?

C. P.: I’ve always been interested in human health. I was going to be a medical researcher early on and I switched. But as soon as I started publishing the results that we were getting on the extent of species movements, the first thing I thought of was, ‘well diseases are going to be moving too’. So my lab’s work on human health focuses on how climate change is affecting where diseases, their vectors, and their reservoirs are spreading. One of my grad students documented the movement of leishmaniasis into Texas, going northward into Texas related to climate change.

In the IPCC we documented malaria, dengue and three other tropical diseases that have moved into Nepal, where they’ve never been before, at least in historical record, and that’s related to climate change, not to agricultural changes.

We also have new diseases emerging in the high Arctic. But not many people live in the high Arctic. It’s the Inuit communities that are being affected, so it gets downplayed by politicians. In Europe,the tiger mosquito is spreading into France, carrying its diseases with it.

Leishmaniasis is also already present in France, one species so far, but predictions suggest that four or five more species could arrive very soon. Tick-borne diseases are also increasing and moving north across Europe. So we are seeing the effect of climate change on human disease risk in Europe right now. People just aren’t aware of it.

You mentioned your family, some of whom are Trump supporters. Are you able to talk about your work with them?

C. P.: In my family, the only option is to not talk about it, and it’s agreed upon by everyone. It’s been that way for a long time about politics, even religion. We all love each other. We want to get along. We don’t want any divisions. So we kind of grow up knowing there are just certain topics you don’t talk about. Occasionally, climate change does come up and it gets difficult and it’s like, that’s why we don’t talk about it. So it’s not been possible to have an open conversation about it. I’m sorry about that, but I’m not going to lose my family. Nor, obviously, just push to convince them. I mean, if they want to know about it, they know where to come.

But I’ve also experienced working with people who have very different beliefs from mine. When I was still in Texas I worked with the National Evangelical Association. We both wanted to preserve biodiversity. They see it as God’s creation, I just think it’s just none of man’s business to destroy the Earth and I am an atheist, but that is fine. We did a series of videos together where I explained the effect of global warming. The result was wonderful.

This article is published as part of the 20th anniversary celebrations of the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR). Camille Parmesan is a winner of the “Make Our Planet Great Again” (MOPGA) program managed by the ANR on behalf of the French government. The ANR’s mission is to support and promote the development of fundamental and applied research in all disciplines, and to strengthen the dialogue between science and society.

Camille Parmesan ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

09.12.2025 à 11:59

Plantes médicinales : valider la tradition, prévenir les risques

Texte intégral (3774 mots)

En France, dans les territoires d’outre-mer en particulier, mais aussi ailleurs dans le monde, l’ethnopharmacologie doit faire face à plusieurs enjeux. Les laboratoires spécialisés dans cette discipline sont sollicités pour confirmer, ou non, l’intérêt thérapeutique de remèdes, à base de plantes notamment, utilisés dans les traditions. Mais ils doivent mener ce travail en préservant ces savoirs dans leurs contextes culturels.

Saviez-vous que près d’une plante sur dix dans le monde était utilisée à des fins médicinales ? Certaines ont même donné naissance à des médicaments que nous connaissons tous : l’aspirine, dérivé du saule (Salix alba L.), ou la morphine, isolée du pavot à opium (Papaver somniferum L.).

Au fil des siècles, les remèdes traditionnels, consignés dans des textes comme ceux de la médecine traditionnelle chinoise ou ayurvédique, ou transmis oralement, ont permis de soulager une multitude de maux. Ainsi, en Chine, les tiges de l’éphédra (Ephedra sinica Stapf), contenant de l’éphédrine (un puissant décongestionnant), étaient employées contre le rhume, la toux et l’asthme il y a déjà 5 000 ans. En Europe, les feuilles de digitale (Digitalis purpurea L.), d’où est extraite la digoxine (un cardiotonique), servaient dès le Moyen Âge à traiter les œdèmes.

En Amérique du Sud, l’écorce du quinquina (Cinchona pubescens Vahl.), contenant de la quinine (antipaludique), étaient utilisées par des communautés indigènes pour combattre les fièvres. En Inde, les racines de rauvolfia (Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz) contenant de la réserpine (antihypertenseur), furent même employées par Mahatma Gandhi pour traiter son hypertension.

Aujourd’hui encore, les plantes médicinales restent très utilisées, notamment dans les régions où l’accès aux médicaments conventionnels est limité. Mais une question demeure : sont-elles toutes réellement efficaces ? Leur action va-t-elle au-delà d’un simple effet placebo ? Et peuvent-elles être dangereuses ?

C’est à ces interrogations que répond l’ethnopharmacologie : une science à la croisée de l’ethnobotanique et de la pharmacologie. Elle vise à étudier les remèdes traditionnels pour en comprendre leurs effets, valider leur usage et prévenir les risques. Elle contribue aussi à préserver et valoriser les savoirs médicinaux issus des cultures du monde.

Un patrimoine mondial… encore peu étudié

Ces études sont d’autant plus cruciales que les plantes occupent encore une place centrale dans la vie quotidienne de nombreuses sociétés. En Afrique subsaharienne, environ 60 % de la population a recours à la médecine traditionnelle. En Asie, ce chiffre avoisine les 50 %. Et en Europe, 35 % de la population française déclare avoir utilisé des plantes médicinales ou d’autres types de médecines non conventionnelles dans les douze derniers mois – l’un des taux les plus élevés du continent !

Cette spécificité française s’explique par un faisceau de facteurs : une culture de résistance à l’autorité (face à la rigidité bureaucratique ou au monopole médical), un héritage rural (valorisation des « simples » de nos campagnes et méfiance envers une médecine jugée trop technologique), mais aussi une ouverture au religieux, au spirituel et au « paranormal » (pèlerinages de Lourdes, magnétisme, voyance…).

Ces chiffres ne reflètent pourtant pas toute la richesse de la phytothérapie française (la phytothérapie correspondant littéralement à l’usage thérapeutique des plantes). Dans les territoires d’outre-mer, les savoirs traditionnels sont particulièrement vivants.

Que ce soit en Nouvelle-Calédonie, où se côtoient traditions kanak, polynésienne, wallisienne, chinoise et vietnamienne, ou en Guyane française, avec les médecines créole, amérindienne, hmong ou noir-marron. Au total, les 13 territoires ultramarins apportent une richesse indéniable à la pharmacopée française. Preuve en est : 75 plantes ultramarines utilisées en Guadeloupe, en Guyane française, à la Martinique et à La Réunion ont récemment été intégrées à la pharmacopée nationale, un document officiel recensant les matières premières autorisées pour la fabrication des médicaments. Parmi elles, le gros thym (Coleus amboinicus Lour.) dont les feuilles sont utilisées pour traiter les rhumatismes, les fièvres ou encore l’asthme dans ces quatre territoires.

Mais cela reste l’arbre qui cache la forêt : sur les quelques 610 plantes inscrites à la pharmacopée française, seules quelques-unes proviennent des territoires ultramarins, alors même que les Antilles, la Guyane française et la Nouvelle-Calédonie comptent chacune environ 600 espèces médicinales recensées par la recherche. Plus largement encore, à l’échelle mondiale, seules 16 % des 28 187 plantes médicinales connues figurent aujourd’hui dans une pharmacopée officielle ou un ouvrage réglementaire. Autrement dit, l’immense majorité de ce patrimoine reste à explorer, comprendre et valoriser.

Étudier, valider, protéger

Dans les pharmacopées officielles, chaque plante fait l’objet d’une monographie : un document scientifique qui rassemble son identité botanique, ses composés bioactifs connus, ses données pharmacologiques et toxicologiques ainsi que les usages traditionnels et établis scientifiquement (indications thérapeutiques, posologies, modes d’administration, précautions d’emploi). En somme, une monographie joue à la fois le rôle de carte d’identité et de notice d’emploi de la plante. Validée par des comités d’experts, elle constitue une référence solide pour les professionnels de santé comme pour les autorités sanitaires.

Lorsqu’une plante n’est pas intégrée dans une pharmacopée, son usage reste donc empirique : on peut l’utiliser depuis des siècles, mais sans données claires sur son efficacité, la sécurité ou les risques d’interactions avec d’autres traitements.

Pour avancer vers la création de monographies et mieux intégrer ces plantes aux systèmes de santé, plusieurs outils sont à notre disposition :

des enquêtes ethnobotaniques, pour recenser les savoirs traditionnels et décrire les remèdes utilisés ;

des tests pharmacologiques, pour comprendre l’effet biologique des plantes et le lien avec leur usage (ex. : une plante utilisée contre les furoncles peut être testée contre le staphylocoque doré) ;

des analyses toxicologiques, pour évaluer l’innocuité des plantes, sur cellules humaines ou organismes vivants ;

des analyses phytochimiques, pour identifier les molécules actives, grâce à des techniques comme la chromatographie ou la spectrométrie de masse.

Au sein de nos laboratoires PharmaDev à Toulouse (Haute-Garonne) et à Nouméa (Nouvelle-Calédonie), nous combinons ces approches pour mieux comprendre les plantes et les intégrer, à terme, dans les systèmes de soins. Nous étudions des pharmacopées issues de Mayotte, de Nouvelle-Calédonie, de Polynésie française, mais aussi du Bénin, du Pérou, du Cambodge ou du Vanuatu.

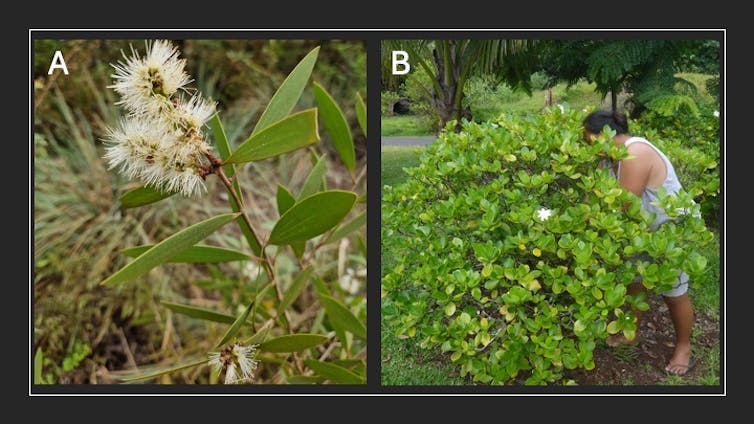

Par exemple, nous avons analysé des remèdes du Pacifique utilisés chez les enfants pour en comprendre les bénéfices thérapeutiques et les risques toxiques. En Nouvelle-Calédonie, les feuilles de niaouli (Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S.T.Blake) sont couramment utilisées contre les rhumes en automédication. Or, elles contiennent de l’eucalyptol, susceptible de provoquer des convulsions chez les enfants de moins de 36 mois. Il est donc recommandé de ne pas employer ce remède chez les enfants de cet âge et/ou ayant eu des antécédents d’épilepsie ou de convulsions fébriles et, en cas de doute, de se référer à un professionnel de santé (médecin, pharmacien…). D’ailleurs, certains médicaments à base d’huile essentielle de niaouli peuvent, en fonction du dosage, être réservés à l’adulte. C’est précisément pour cela que nous diffusons nos résultats à travers des articles scientifiques, des séminaires et des livrets de vulgarisation, afin que chacun puisse faire un usage éclairé de ces remèdes.

Médecine traditionnelle et enjeux de développement durable

En Polynésie française, nous étudions la médecine traditionnelle à travers le développement durable. Plusieurs menaces pèsent aujourd’hui sur ces pratiques : la migration des jeunes, qui fragilise la transmission intergénérationnelle des savoirs ; le changement climatique, qui modifie la répartition des plantes ; ou encore les espèces invasives, qui concurrencent et parfois supplantent les espèces locales.

Or, ces savoirs sont essentiels pour assurer un usage sûr et efficace des plantes médicinales. Sortis de leur contexte ou mal interprétés, ils peuvent conduire à une perte d’efficacité, voire à des intoxications.

Un exemple concret est celui du faux-tabac (Heliotropium arboreum), ou tahinu en tahitien, dont les feuilles sont traditionnellement utilisées dans le traitement de la ciguatera, une intoxication alimentaire liée à la consommation de poissons, en Polynésie et ailleurs dans le Pacifique. Des études scientifiques ont confirmé son activité neuroprotectrice et identifié la molécule responsable : l’acide rosmarinique. Mais une réinterprétation erronée de ces résultats a conduit certaines personnes à utiliser l’huile essentielle de romarin. Or, malgré son nom, cette huile ne contient pas d’acide rosmarinique. Résultat : non seulement le traitement est inefficace, mais il peut même devenir toxique, car les huiles essentielles doivent être manipulées avec une grande précaution.

Cet exemple illustre un double enjeu : la nécessité de préserver les savoirs traditionnels dans leur contexte culturel et celle de les valider scientifiquement pour éviter les dérives.

En ce sens, la médecine traditionnelle est indissociable des objectifs de développement durable : elle offre une approche biologique, sociale, psychologique et spirituelle de la santé, elle permet de maintenir les savoirs intergénérationnels, de valoriser la biodiversité locale et de réduire la dépendance aux médicaments importés.

C’est dans cette perspective que notre programme de recherche s’attache à identifier les menaces, proposer des solutions, par exemple en renforçant les liens intergénérationnels ou en intégrant les connaissances sur les plantes dans le système scolaire, et à valider scientifiquement les plantes les plus utilisées.

François Chassagne a reçu des financements de l'ANR (Agence Nationale de la Recherche)

08.12.2025 à 11:46

Atteindre la neutralité carbone exigera 3 859 milliards d’euros par an jusqu’en 2050

Texte intégral (1556 mots)

Comment récolter cette somme colossale ? Une étude menée auprès de 42 pays souligne que la stabilité institutionnelle permet d’assurer le développement de la finance verte. Ses conclusions sont nettes et sans bavure : les pays avec un cadre réglementaire solide s’en sortent le mieux.

La planète réclame une facture colossale : 3 859 milliards d’euros par an jusqu’en 2050 pour éviter le chaos climatique, selon l’Agence internationale de l’énergie. L’écart reste abyssal entre cette urgence climatique et les capitaux levés pour financer cette transition.

Notre étude couvrant 42 pays entre 2007 et 2023 rappelle une bonne nouvelle : la finance verte se déploie durablement là où les États offrent un cadre clair et cohérent.

Comment, concrètement, fonctionne cette corrélation?

Réduire l’incertitude

Nos résultats montrent que plus un pays adopte des politiques environnementales ambitieuses, plus le volume d’obligations vertes émises sur son territoire augmente.

L’indice utilisé dans cette étude, fondé sur les données de l’Agence internationale de l’énergie, recense l’ensemble des mesures environnementales adoptées dans le monde. Il correspond au nombre total de lois, réglementations et plans d’action environnementaux en vigueur dans chaque pays. Plus ce stock de règles est élevé, plus le cadre climatique national apparaît développé, prévisible et crédible pour les investisseurs.

Ce lien s’explique par un mécanisme simple : un environnement réglementaire clair réduit l’incertitude sur les futures politiques climatiques. Les émetteurs d’obligations vertes savent quelles activités seront financées, tandis que les investisseurs disposent d’un cadre pour évaluer la rentabilité des projets. De facto, la demande d’obligations vertes croît, réduit leur prime de risque, et stimule mécaniquement leur volume d’émission.

L’Europe en pointe

Cette dynamique se vérifie particulièrement en Europe. Selon l’Agence européenne de l’environnement, la part des obligations vertes dans l’ensemble des obligations émises par les entreprises et les États de l’Union européenne est passée d’environ 0,1 % en 2014 à 5,3 % en 2023, puis 6,9 % en 2024.

Dans ce contexte, la taxonomie verte européenne et le reporting obligatoire sur les risques climatiques et les indicateurs ESG – CSRD, SFDR– instaurent un cadre d’investissement harmonisé, facilitant l’allocation de capitaux vers les actifs verts.

À lire aussi : À quoi servent les obligations vertes ?

La France illustre cette dynamique européenne. Elle ouvre la voie dès 2017 avec une obligation verte de sept milliards d’euros sur vingt-deux ans, émise par l’Agence France Trésor. Selon une étude de la Banque de France, les obligations souveraines vertes de la zone euro offrent en moyenne un rendement inférieur de 2,8 points de base (0,028 point de pourcentage) à celui d’obligations souveraines classiques comparables. Cet écart, faible mais régulier, est interprété par la Banque de France comme une « prime verte ». Concrètement, les investisseurs acceptent de gagner un peu moins pour détenir des titres verts.

La Chine rattrape son retard

À ce jour, les gouvernements du monde entier ont adopté environ 13 148 réglementations, cadres et politiques visant à atteindre la neutralité carbone d’ici 2050.

En Chine, les réformes des critères ESG en 2021 et 2022, ainsi que leur alignement avec les standards internationaux, ont placé le pays parmi les tout premiers émetteurs mondiaux d’obligations vertes, selon la Climate Bonds Initiative. En Afrique du Nord, l’Égypte s’est lancée avec une première obligation souveraine verte en 2020, soutenue par la Banque mondiale.

Dans ces économies, un cadre réglementaire stable est également associé, dans nos données, à des maturités moyennes pondérées plus longues pour les obligations vertes. Lorsque le cadre réglementaire se renforce, les obligations vertes présentent en moyenne des échéances de dix à vingt ans, plutôt que de quelques années seulement. L’enjeu : financer des projets de long terme, comme des infrastructures énergétiques ou de transport.

L’Italie, l’Espagne, l’Inde et l’Indonésie vulnérables

L’effet des politiques climatiques sur la finance verte est particulièrement marqué dans les économies « vulnérables sur le plan énergétique ». Dans notre étude, nous avons utilisé deux indicateurs : la part des importations nettes d’énergie dans la consommation nationale et l’intensité énergétique (consommation d’énergie rapportée au PIB).

À titre d’illustration, des pays européens fortement importateurs d’énergie, comme l’Italie ou l’Espagne, et des économies émergentes à forte intensité énergétique, comme l’Inde ou l’Indonésie, présentent ce profil de vulnérabilité.

Nous classons ensuite les pays de notre échantillon selon leur degré de vulnérabilité énergétique à partir de ces deux indicateurs. Lorsque l’on compare l’évolution des émissions d’obligations vertes dans les économies les plus vulnérables à celle observée dans les autres pays de l’échantillon, on constate qu’un même durcissement des politiques climatiques s’y traduit par une augmentation nettement plus rapide du recours à la finance verte.

Réduire la dépendance aux énergies fossiles

En Europe, la crise énergétique de 2022 et le lancement de REPowerEU ont profondément reconfiguré le lien entre politique climatique et sécurité énergétique.

Face à la flambée des prix du gaz, l’Union européenne a accéléré la réduction de sa dépendance aux combustibles fossiles importés. Selon le Conseil de l’Union européenne, la part du gaz russe dans ses importations de gaz est passée de plus de 40 % en 2021 à environ 11 % en 2024 pour le gaz acheminé par gazoducs ; à moins de 19 % si l’on inclut le gaz naturel liquéfié. Dans le même temps, la capacité solaire de l’Union européenne a presque triplé depuis 2019 pour atteindre un peu plus de 300 GW en 2024, et les énergies renouvelables ont fourni près de 47 % de l’électricité européenne.

Ces transformations s’accompagnent d’un effort d’investissement massif. La Commission européenne a décidé de lever jusqu’à 30 % du plan NextGenerationEU sous forme d’« obligations vertes NextGenerationEU », soit un volume potentiel d’environ 225 milliards d’euros. De leur côté, plusieurs États membres ont mis en place des programmes souverains importants : en France, l’encours des obligations assimilables du Trésor vertes (OAT vertes) atteignait environ 70 milliards d’euros fin 2023.

Pour les décideurs, l’enjeu n’est donc pas de multiplier les annonces, mais de fixer un cap crédible dans la durée.

Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.