10.02.2026 à 14:11

Les chiens et les chats transportent les vers plats envahissants de jardin à jardin

Texte intégral (1261 mots)

Les chiens et les chats domestiques peuvent transporter les vers plats (plathelminthes) collés sur leur pelage. Sans le vouloir, ils contribuent ainsi à la propagation de ces espèces exotiques envahissantes. Notre travail vient d’être publié dans la revue scientifique PeerJ.

Au niveau mondial, les espèces exotiques intrusives représentent un des dangers majeurs pour la biodiversité. Il est frappant de découvrir que les chiens et les chats, nos compagnons du quotidien, participent de manière involontaire à l’envahissement des jardins par une espèce potentiellement dangereuse pour la biodiversité.

Comment avons-nous fait cette découverte ?

Nous menons un projet de sciences participatives sur les invasions de vers plats.

Nous avons été interpellés par des courriels envoyés par des particuliers signalant la présence de vers collés au pelage de chiens et de chats. Nous avons alors réexaminé plus de 6 000 messages reçus en douze ans et avons constaté que ces observations étaient loin d’être anecdotiques : elles représentaient environ 15 % des signalements.

Fait remarquable, parmi la dizaine d’espèces de vers plats exotiques introduits en France, une seule était concernée : Caenoplana variegata, une espèce venue d’Australie dont le régime alimentaire est composé d’arthropodes (cloportes, insectes, araignées).

En quoi cette découverte est-elle importante ?

On sait depuis longtemps que les plathelminthes (vers plats) exotiques sont transportés de leur pays d’origine vers l’Europe par des moyens liés aux activités humaines : conteneurs de plantes acheminés par bateau, camions livrant ensuite les jardineries, puis transport en voiture jusqu’aux jardins.

Ce qu’on ne comprenait pas bien, c’est comment les vers plats, qui se déplacent très lentement, pouvaient ensuite envahir les jardins aux alentours. Le mécanisme mis en évidence est pourtant simple : un chien (ou un chat) se roule dans l’herbe, un ver se colle sur le pelage, et l’animal va le déposer un peu plus loin. Dans certains cas, il le ramène même chez lui, ce qui permet aux propriétaires de le remarquer.

Par ailleurs, il est surprenant de constater qu’une seule espèce est concernée en France, alors qu’elle n’est pas la plus abondante. C’est Obama nungara qui est l’espèce la plus répandue, tant en nombre de communes envahies qu’en nombre de vers dans un jardin, mais aucun signalement de transport par animal n’a été reçu pour cette espèce.

Cette différence s’explique par leur régime alimentaire. Obama nungara se nourrit de vers de terre et d’escargots, tandis que Caenoplana variegata consomme des arthropodes, produisant un mucus très abondant et collant qui piège ses proies. Ce mucus peut adhérer aux poils des animaux (ou à une chaussure ou un pantalon, d’ailleurs). De plus, Caenoplana variegata se reproduit par clonage et n’a donc pas besoin de partenaire sexuel : un seul ver transporté peut infester un jardin entier.

Nous avons alors tenté d’évaluer quelles distances parcourent les 10 millions de chats et les 16 millions de chiens de France chaque année. À partir des informations existantes sur les trajets quotidiens des chats et des chiens, nous avons abouti à une estimation spectaculaire : des milliards de kilomètres au total par an, ce qui représente plusieurs fois la distance de la Terre au Soleil ! Même si une petite fraction des animaux domestiques transporte des vers, cela représente un nombre énorme d’occasions de transporter ces espèces envahissantes.

Un point à clarifier est qu’il ne s’agit pas de parasitisme, mais d’un phénomène qui s’appelle « phorésie ». C’est un mécanisme bien connu dans la nature, en particulier chez des plantes qui ont des graines collantes ou épineuses, qui s’accrochent aux poils des animaux et tombent un peu plus loin. Mais ici, c’est un animal collant qui utilise ce processus pour se propager rapidement.

Quelles sont les suites de ces travaux ?

Nous espérons que cette découverte va stimuler les observations et nous attendons de nouveaux signalements du même genre. D’autre part, nos résultats publiés concernent la France, pour laquelle les sciences participatives ont fourni énormément d’informations, mais quelques observations suggèrent que le même phénomène existe aussi dans d’autres pays, mais avec d’autres espèces de vers plats.

Il est désormais nécessaire d’étendre ces recherches à l’échelle internationale, afin de mieux comprendre l’ampleur de ce mode de dispersion et les espèces concernées.

Tout savoir en trois minutes sur des résultats récents de recherches commentés et contextualisés par les chercheuses et les chercheurs qui les ont menées, c’est le principe de nos « Research Briefs ». Un format à retrouver ici.

Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.

10.02.2026 à 12:55

« Trump est fou » : les effets pervers d’un pseudo-diagnostic

Texte intégral (3562 mots)

Qualifier Donald Trump de « fou », comme c’est régulièrement le cas ces derniers temps, tend à détourner l’attention de la cohérence de la politique conduite par l’intéressé depuis son retour à la Maison-Blanche et du fait qu’il constitue moins une anomalie individuelle qu’un produit typique d’un système économique, médiatique et culturel qui valorise la domination, la spectacularisation et la marchandisation du monde. Il convient de se détourner de cette psychologisation à outrance pour mieux se concentrer sur les structures sociales qui ont rendu possible l’accession au pouvoir d’un tel individu.

C’est devenu en quelques jours du mois de janvier 2026 la note la plus tenue de l’espace médiatique : Trump est fou. Une élue démocrate au Congrès des États-Unis tire la sonnette d’alarme sur X, le 19 janvier : le président est « mentalement extrêmement malade », affirme-t-elle. Fox News, média proche de Donald Trump sur le long terme, reprend les propos dès le lendemain sur un ton factuel. Le 22 janvier, lendemain du discours de Trump à Davos, durant lequel il a demandé « un bout de glace » (à savoir le Groenland) « en échange de la paix mondiale », l’Humanité fait le titre de sa une avec un magnifique jeu de mots : Trump « Fou allié ».

Le 23 janvier, des messageries relayent ce qui déjà se diffuse largement dans la presse : « Déclaration de représentants démocrates au Congrès US : la santé mentale de Donald Trump est altérée ; c’est pire que Joe Biden, c’est un cas de démence ».

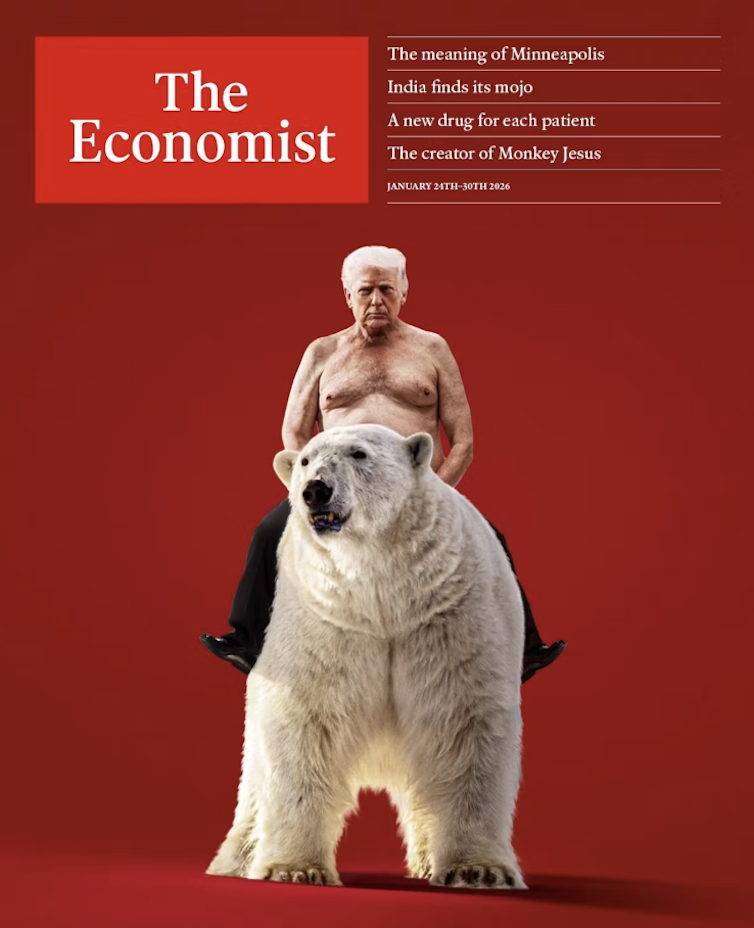

Le 24 janvier, la une de l’hebdomadaire The Economist montre un Donald Trump torse nu à califourchon sur un ours polaire – message de folle divagation en escalade mimétique avec Poutine et ses clichés poitrine à l’air, l’animal du Grand Nord soulignant en l’occurrence les prétentions du locataire de la Maison Blanche sur le Groenland.

Même le premier ministre slovaque Robert Fico, pourtant un allié du milliardaire new-yorkais, l’aurait jugé « complètement dérangé » après l’avoir rencontré le 19 janvier à Mar-a-Lago. Le cas Trump est donc désormais régulièrement examiné à l’aune de la folie par des élus, des journalistes, mais aussi des psychiatres.

Il y a pourtant matière à être dubitatif sur les accusations de folie portées contre Trump. Non seulement elles n’ont guère contribué jusqu’ici à le neutraliser, mais elles ont même fait son succès et empêchent de penser le vrai problème. Les arguments en leur défaveur méritent un tour d’horizon.

Quelle légitimité du discours médicalisant ?

Il peut sembler contestable, même quand on est psychiatre et a fortiori quand on ne l’est pas, de déclarer quelqu’un malade mental sans l’avoir examiné selon des protocoles précis.

Quand le 5 mars 2025 le sénateur français Claude Malhuret, qui est médecin, traite Trump de « Néron » et de « bouffon » à la tribune du palais du Luxembourg – une intervention qui deviendra virale aux États-Unis –, le discours est de belle facture rhétorique, mais il n’est pas médical.

Le sénateur ne se réfère d’ailleurs pas à l’Académie. À ce stade, en l’absence d’examen effectué par des professionnels dont les résultats auraient été rendus publics, qualifier Trump de fou relève plus de la tournure politique que médicale.

Une rhétorique inefficace

Les déclarations sur la folie de Trump se succèdent sur le long cours sans avoir montré la moindre efficacité pour le combattre. Dès la première année de son premier mandat, la rumeur bruisse d’une possible destitution pour raison mentale sur la base d’avis d’experts qui n’ont pourtant pas eu d’entretiens avec le principal intéressé. Aucune procédure de destitution ne sera engagée sur ces bases.

Une nouvelle sortie collective de professionnels sur le déclin cognitif de Trump, lui trouvant un « désordre sévère et incurable de la personnalité », eut lieu en octobre 2024. Ce qui ne l’empêcha pas d’être élu assez aisément le mois suivant face à Kamala Harris. Quant à la défaite de 2020, elle arriva en pleine vague Covid et fut moins la conséquence des assertions selon lesquelles le président sortant était fou que de sa gestion désastreuse de la pandémie : sous-estimation de l’ampleur des contagions et de la mortalité, refus ostensible du port du masque.

Un jour, sans doute, Trump quittera-t-il le pouvoir, mais les effets des jugements de maladie mentale sur sa carrière politique – et en particulier sur sa victoire de 2024, qui se produisit alors que les électeurs avaient toute connaissance de son profil personnel – ont été nuls jusqu’à aujourd’hui.

Des attaques qui font le jeu de Trump

Pis encore : ces attaques ne sont pas seulement inefficaces, elles servent Trump. Le cœur de sa technique – qu’il a explicitée dès les années 1980 dans The Art of the Deal – consiste à semer la controverse pour faire parler de lui et de ses projets. Lui répondre sur ce terrain qui est le sien, en le traitant notamment de psychopathe (ou d’aberrant, de monstrueux, de stupide, ou de lunaire – le dernier vocable à la mode), c’est tomber dans le piège : il se pose ensuite en victime et ramasse les suffrages. Le sujet d’étonnement est que, depuis dix ans, aucune leçon n’ait été tirée de ces échecs à répétition dans la lutte contre Trump.

« Je fulmine et m’extasie comme un dément, et plus je suis fou, plus l’audimat grimpe »,

s’autopitchait Trump pour son émission de téléréalité, The Apprentice (source : Think Big and Kick Ass: In Business and Life, D. Trump et B. Zanker, 2007). Folie ? Non. Mise en scène éprouvée qui attire l’attention à son profit.

Mais le bénéfice s’enclenche aussi pour les commentateurs et les chambres d’écho. Et c’est là que le bât blesse : les « coups de folie » de Trump sont en réalité des diversions où les médias, les oppositions, les politiques et, souvent, les experts s’engouffrent pour le buzz.

Trump est à l’image de la société

Au-delà de la télé, les méthodes de Trump sont typiques de conseils de vie qui circulent largement dans la société, émanant de bien d’autres agents que lui. On pense, par exemple, aux classiques Swim With the Sharks Without Being Eaten Alive (1988), de Harvey Mackay, ou The Concise 33 Strategies of War (2006), de Robert Greene.

On pense aussi aux métaphores guerrières qui se glissent dans des ouvrages de management plus pondérés ; « les salles de commandement en temps de guerre » décrivent les réunions des équipes « successful », dans X-Teams (2007) ; donner plus de pouvoir au manager est recommandé pour qu’il ne se retrouve pas « face à dix ennemis avec une seule balle dans son fusil », dans Smart simplicity (2014).

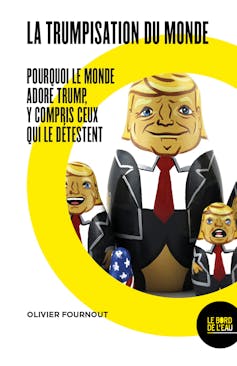

De ce point de vue, Trump est « banal, trop banal ». Il est typique d’une « héroïcomanie hypermoderne », porté par une « trumpisation du monde » qui le dépasse. La conséquence de ce constat sociologique est que le problème est beaucoup plus profond qu’une folie idiosyncrasique, si perturbante soit-elle.

Déclarer Trump fou fait oublier à quel point le mode opératoire trumpiste est, pour une part non négligeable, partagé transversalement par la société. Ainsi, Trump privilégie-t-il les rapports de force. Il a toujours été sans équivoque sur ce point qui lui apporta la réussite dans le business, la télévision, le marché du leadership, et maintenant en politique. Mais cela ne se réalise pas contre la société américaine, comme par accident, mais en miroir d’un vaste spectre de celle-ci.

La négociation le revolver sur la tempe alimente quantité de traités de développement personnel, de management et de communication au travail. Elle est la matrice scénaristique assurant la popularité des films hollywoodiens (non seulement les westerns mais aussi les « propositions qui ne se refusent pas » du film le Parrain). Rien, là, de fou ou d’aberrant. Juste un éthos dominant qui a sa rationalité et qui n’a jamais été soft.

Aussi, aucune surprise si la rencontre d’un pouvoir fort est seule susceptible de faire fléchir Trump. Là encore, il est explicite sur ce point depuis longtemps. Lorsqu’il fut proche de la faillite dans les années 1990, il courbe l’échine devant les banquiers : « Quand vous devez de l’argent à des gens, vous allez les voir dans leur bureau […] Je voulais faire n’importe quoi sauf aller à des dîners avec des banquiers, mais je suis allé dîner avec des banquiers » (in Think big, 2007). Rationalité strictement instrumentale, certes, mais rationalité. L’article de fond « Ice and heat » récemment publié par The Economist sur l’affaire du Groenland relève que la menace européenne de déclencher l’instrument anti-coercition a joué, pour l’instant, dans le recul de Trump.

Révéler la structure pour mieux la combattre

Pour contrer l’Amérique de Trump, il conviendrait d’abord plutôt de se pencher sur la rationalité de ses lignes directrices. Son action, aussi bien en diplomatie qu’en politique intérieure, aussi bien en politique économique qu’en gestion des ressources naturelles, découle d’une stratégie claire et constante, pensée et volontariste. C’est sur ce terrain qu’il faut se battre pour défaire Trump, et non par des coups d’épée dans l’eau qui donnent bonne conscience à bon compte, sont repris en boucle, mais n’apportent rien de consistant face au fulminant showman.

Du discours de Trump à Davos, le 21 janvier 2026, ressortent plusieurs traits qui n’ont rien de mentalement dérangé. D’une part, il apporte un momentum aux extrêmes droites européennes déjà au pouvoir ou aux portes de celui-ci. D’autre part, une Europe qui se réarme et qui reste toujours globalement « alliée » des États-Unis débouche sur une situation stratégique plus favorable du point de vue américain : tel est le résultat, objectif, de la séquence historique actuelle.

Enfin, la demande d’avoir un « titre de propriété » sur le Groenland réussit à installer, même si elle n’aboutit pas, l’horizon indépassable du monde selon Trump : « La terre, comme les esclaves d’Ulysse, reste une propriété », comme l’écrivait Aldo Leopold, pionnier de la protection de la nature aux États-Unis, dans Almanach d’un comté des sables, publié en 1948 (traduction française de 2022 aux éditions Gallmeister). Trump est dans son élément, en parfaite maîtrise du vocabulaire pour fragiliser la transition ou bifurcation écologique. Comme l’exprime Estelle Ferrarese dans sa critique de la consommation éthique, « dans aucun cas la finalité n’est de mettre certaines choses (comme la terre) hors marché ».

Question ouverte pour l’Histoire

En insistant sur la supposée folie de Trump, les commentaires se rabattent sur un prisme psychologisant individuel. Peut-être Trump est-il fou. La sénilité peut le guetter – il en a l’âge. Des centaines de pathologies psychiatriques sont au menu des possibles qui peuvent se combiner.

Mais l’analyse et l’inquiétude ont à se pencher, en parallèle, sur le symptôme structurel de notre temps, sur ce système qui, depuis cinquante ans, propulse Trump au zénith des affaires, des médias, des ventes de conseils pour réussir, et deux fois au sommet du pouvoir exécutif de la première puissance mondiale.

La prise de distance avec l’accusation de folie portée contre Trump ouvre un chantier de réflexion où le problème n’est plus la folie personnelle du leader élu, mais une stratégie dont Trump est, en quelque sorte, un avatar extrême mais emblématique. Le regard se détache de l’événementiel chaotique – trumpiste ou non trumpiste – pour retrouver le fil d’une analyse structurelle. Sans conteste, Trump fragilise l’ONU et l’OMS, mais à l’aune de l’histoire longue, il ressort qu’une « impuissance structurelle » persévère, selon laquelle « dans le cas des États-Unis, c’est un grand classique que de bouder (au mieux) et de torpiller (autant que possible) toutes les démarches multilatérales dont ils n’ont pas pris l’initiative ou qu’ils ne sont pas (ou plus) capables de contrôler » (Alain Bihr, l’Écocide capitaliste, tome 1, 2026, p. 249).

Les psychés peuvent être « débridées », mais ce sont les « structures sociales » qui « sélectionnent les structures psychiques qui leur sont adéquates ». Trump n’est plus alors une anomalie foutraque, sénile, troublée, en rupture avec ce qui a précédé et à côté des structures sociales, mais la poursuite d’une marchandisation du monde à haut risque, dont le diagnostic est à mettre en haut des médiascans, pour discussion publique.

Olivier Fournout ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

- GÉNÉRALISTES

- Ballast

- Fakir

- Interstices

- Issues

- Korii

- Lava

- La revue des médias

- Time [Fr]

- Mouais

- Multitudes

- Positivr

- Regards

- Slate

- Smolny

- Socialter

- UPMagazine

- Le Zéphyr

- Idées ‧ Politique ‧ A à F

- Accattone

- À Contretemps

- Alter-éditions

- Contre-Attaque

- Contretemps

- CQFD

- Comptoir (Le)

- Déferlante (La)

- Esprit

- Frustration

- Idées ‧ Politique ‧ i à z

- L'Intimiste

- Jef Klak

- Lignes de Crêtes

- NonFiction

- Nouveaux Cahiers du Socialisme

- Période

- ARTS

- L'Autre Quotidien

- Villa Albertine

- THINK-TANKS

- Fondation Copernic

- Institut La Boétie

- Institut Rousseau

- TECH

- Dans les algorithmes

- Framablog

- Gigawatts.fr

- Goodtech.info

- Quadrature du Net

- INTERNATIONAL

- Alencontre

- Alterinfos

- Gauche.Media

- CETRI

- ESSF

- Inprecor

- Guitinews

- MULTILINGUES

- Kedistan

- Quatrième Internationale

- Viewpoint Magazine

- +972 mag

- PODCASTS

- Arrêt sur Images

- Le Diplo

- LSD

- Thinkerview