Leading by example? How the private jets at Davos send a devastating message to future generations

Jackie Zamora

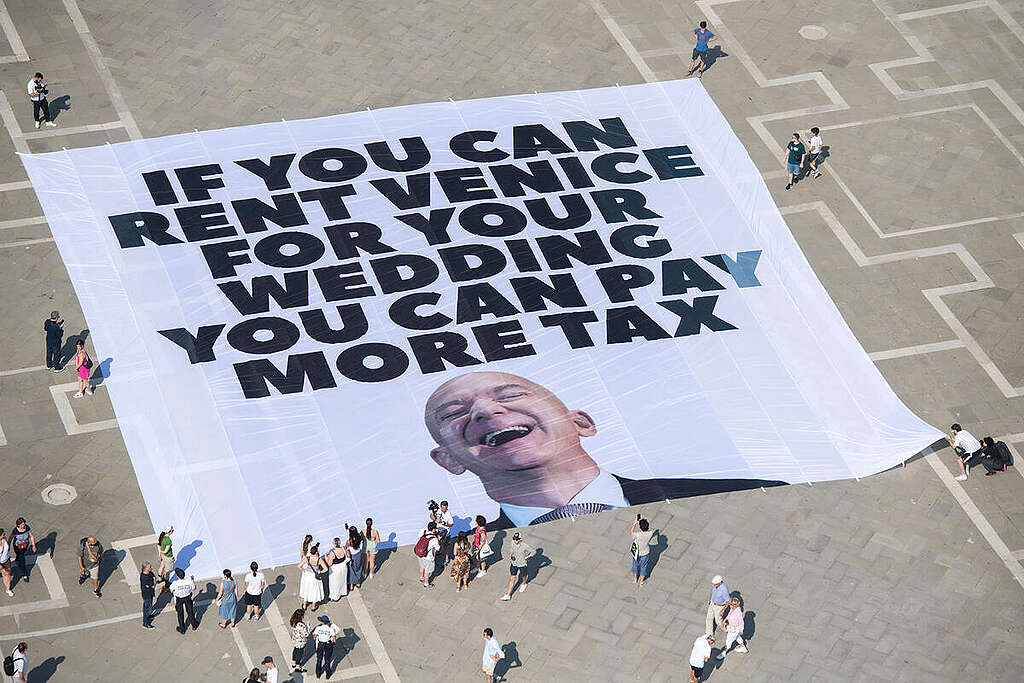

While families around the world are facing the impacts of the climate and nature crises in their communities, some of the world’s most powerful leaders are attending the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland in the most polluting and most unequal form of transport: private jets. What does this teach our children about responsibility and fairness? Every January, world leaders and corporate figures meet for the World Economic Forum to discuss the issues facing our world. This year, the main themes are climate and inequality. Attendees are mostly delegates from global businesses, governments, civil society and academia representatives. Ultimately, the goal of Davos forum is to have a dialogue on global challenges and develop tangible solutions to “improve the state of the world.” On paper it sounds good, right? However, before the climate talks even begin, many of these leaders are arriving to the Davos forum on private jets. The number of these flights is increasing every year at an alarming rate. New analysis from Greenpeace CEE reveals that private jet flights to Davos have tripled since 2023 and risen 10% compared with last year. Around 70% of the private jet routes could have been travelled by train within a day or with a night train and connection train. When world leaders arrive by hundreds of private jets to a forum meant to protect the future of younger generations, they send a heartbreaking message to kids everywhere: that our children’s tomorrow does not matter as much as adult convenience today. Even worse, many of the private jets swarming Davos are reportedly chartered or owned by ultra-wealthy individuals. Data shows that billionaires, on average, pay much lower effective tax rates than the rest of us, meaning the richest people often contribute less proportionally while benefiting from systems that impact our children’s future. According to Oxfam, the number of billionaires surpassed 3,000 for the first time last year, and the level of billionaire wealth is now higher than at any time in history. Meanwhile, one in four people globally face hunger and children around the world are significantly impacted by extreme weather events and climate change. Taxes can fund sustainable public transport, classrooms, doctors, and a liveable planet, yet through loopholes and special breaks, the super-rich are allowed to give far less than they can and should. This leaves families around the world to shoulder the cost through punitive taxes and austerity measures that cripple social services, while young people are learning that greed and self-interest comes before community and integrity. When governments don’t tax the super-rich fairly they are allowing resources to be drained from the younger generations and the systems that are supposed to keep them safe and allow them to thrive. When world leaders fail to lead by example, we have a responsibility to hold them accountable. We urge governments to support fair global tax rules to protect the future of children and the planet. Billions in public funds generated from a modest 1-2% tax on the ultra-wealthy could fund universal basic services such as green affordable housing, sustainable heating and cooling, quality healthcare, and public transport, creating a safer, cleaner world for everyone. Children are intelligent and perceptive. They see, hear and feel everything that happens around them, and they are trusting us grown-ups to do the right thing: to be courageous, to keep them safe and to stand up for protecting the planet they will inherit. It’s important that our kids know that many young people are making themselves heard for our planet, and they can too! If they show interest or curiosity, we have free educational resources available to them to learn, explore and take action. We must not give up, and there is still time to act! Discuss with them positive and inspiring stories around the world or in your own community. Together we can act for fairness and achieve a future they can look forward to with hope. Together, let’s urge governments to tax the super-rich and fund a green and fair future. Texte intégral (1746 mots)

What happens at Davos?

Mixed signals and misplaced money

It doesn’t have to be this way

Educational resources for parents and educators

Greenpeace Denmark statement on Greenland

Greenpeace International

Greenpeace Denmark shared the following statement on Greenland on 15 January 2026. Copenhagen, Denmark – Greenpeace Nordic deeply deplores the continued hostility and threats issued towards the people of Greenland by President Donald Trump, his administration and circle of advisors. The people of Greenland must have the right to peacefully determine their own future free from coercion and violence. Regardless of the Trump-regime’s misguided concerns for international security or its desire to pillage and plunder for rare-earth minerals or other resources, the Trump administration needs to be held accountable by the constitutional statutes of the US and the international community. With the recent, illegal military intervention in Venezuela fresh in mind, and the blatant threats towards the people of Greenland, the international community must now act decisively to uphold international law and prevent further harm. ENDS Contact: Greenpeace International Press Desk: +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org (171 mots)

Follow the oil: The logic behind Trump’s first year, foreign policy chaos

John Noel

It feels like a decade…But somehow, Donald Trump has only just clocked one year back in the White House. From intervention in Venezuela to threats against Greenland, from trade tariffs against allies to rambling letters to other Heads of State, it’s an extraordinary and growing list. Once your head stops spinning from the daily deluge of ridiculousness, you can step back and note a common thread running through the madness once you follow the money and the interests behind Trump’s rhetoric. While many were basking in the aftermath of New Year celebrations, US forces were descending into Venezuela to abduct a leader while leaving his regime very much intact. While the US administration suggested an initial rationale of curbing the flow of drugs into the US, the facade soon dropped with Trump declaring control over resources, and in particular oil. “At least US$100 billion will be invested by Big Oil,” Trump said ahead of a White House meeting with representatives of major oil and gas corporations. Trump added that the US and Venezuela were “working well together” to rebuild the nation’s dilapidated oil and gas infrastructure. Despite claiming “US first”, Trump’s actions expose an intent to put the wealth and power of a tiny group of fossil fuel interests and ultra wealthy elites ahead of the wellbeing of US citizens, and the sovereignty and future of people in the countries where he meddles. This is about who controls resources, who profits from them, and who pays the price. Venezuela holds the largest proven crude oil reserves in the world and has long been a target of external pressure, sanctions and geopolitical interference. Trump’s move is the latest intervention in a long pattern of strategic meddling. The Trump administration has tried to portray the move as bolstering US energy security and weakening rivals, but the reality is very different. US households are unlikely to experience any relief at the pump from these interventions. Global crude markets in 2025 already had a surplus of supply over demand, meaning oil prices were low despite a lack of production in Venezuela. And even the most conservative estimates suggest that the Venezuelan oil industry requires investment of more than US$100 billion just to get back to the levels of decades ago. In Trump’s US, it is likely that taxpayers will be on the hook for these costs as Trump socialises the costs to subsidise the private businesses of his donors and supporters. Funneling billions into fossil fuel infrastructure will deepen the global dependence on oil and gas that is driving the climate crisis and biodiversity loss, even when the science tells us there is no room in a safe future for new fossil fuel development. The human costs of resource-driven foreign policy are profound. Military solutions tied to resource control are fundamentally incompatible with international law, human rights, and climate justice. People around the world are already paying the price for decisions made in boardrooms and political offices far from their communities. But as Trump pushes for control of Venezuela’s oil, others are working towards an alternative vision: a world that moves beyond fossil fuels rather than fighting over them. In April, Colombia will host the First International Conference on the Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels, co-organised with the Netherlands, bringing together governments, Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendant communities and climate advocates to chart a just transition away from oil, gas and coal. The conference is not about who controls oil reserves, but who shapes our future. The era of fossil fuels must end if we are to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of the climate crisis. What we’re seeing is not random chaos. It’s a clash between two very different visions of the future; one anchored in old power structures built on fossil fuel domination, and the other rooted in climate justice, and sustainable energy for all. People and planet deserve a foreign policy that reflects their interests, peace, safety, economic security, and a stable climate. Reclaim the moral compass: a call for courageous leaders John Noel is a Senior Strategist with Greenpeace International. Texte intégral (1291 mots)

Reclaim the moral compass: a call for courageous leaders

Greenpeace International

To leaders at all levels of government, business, and institutions: We write from many places, in many languages, with one shared hope: to live in a world where peace is the norm, the climate is stable, and our children inherit a future that is brighter than our present. You have a responsibility to reclaim the moral compass. Peace is not a prize, it is a human right. True leadership is built on solidarity, not threats. A healthy society isn’t measured by the profits of a few, but by the well-being of the many. Success isn’t about who wins, it’s about who thrives. We are defined by what we save, not what we take. Donald Trump has said “My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.” He and his circle of emboldened autocrats backed by polluting empires and their billionaire owners threaten our shared future. We, the people, across generations and borders, call on leaders everywhere to reclaim the moral compass: This is the responsibility of true and courageous leadership in our time: to resist the billionaire takeover of our culture and future, to rise above the hateful rhetoric of division, and to renew our commitment to decency and each other. We, the people, rally behind leaders who are brave enough to reclaim the moral compass. It will take all of us to break through the fear and noise and show our leaders a better path Texte intégral (536 mots)

Bon Pote

Actu-Environnement

Amis de la Terre

Aspas

Biodiversité-sous-nos-pieds

Bloom

Canopée

Décroissance (la)

Deep Green Resistance

Déroute des routes

Faîte et Racines

Fracas

F.N.E (AURA)

Greenpeace Fr

JNE

La Relève et la Peste

La Terre

Le Lierre

Le Sauvage

Low-Tech Mag.

Motus & Langue pendue

Mountain Wilderness

Negawatt

Observatoire de l'Anthropocène