Texte intégral (1693 mots)

This story was originally posted by Greenpeace Argentina in Spanish.

Clearing and deforestation are aggressively advancing on the native forests of northern Argentina, according to a recent report from Greenpeace Argentina based on satellite monitoring imagery.

To understand the magnitude of the damage caused, the images below show some of the highlights from this new investigation along with part of the photographic survey of cleared areas.

During 2023, 126,149 hectares of native forests were lost in the north of the country, 6.2% more than in 2022.

It’s clear that there was an increase in land clearings last year, especially illegally.

100% of the clearings in Chaco and 80% of the clearings in Santiago del Estero were illegal.

The main cause of the loss of native forests in Argentina is the growth of the agricultural industry, mainly for intensive livestock farming and genetically modified soybeans, which are mostly exported to Asia and Europe.

The increasing levels of deforestation in Argentina and around the world intensify the consequences of climate change, which range from more and frequent extreme weather events, to the extinction of species, displacement of native and Indigenous communities and impacts on human health.

Meri Castro is a Digital Content Creator at Greenpeace Andino.

Texte intégral (1520 mots)

Oceans are life and all life is connected.

Wherever we live, we need the oceans. And the oceans need all of us, everywhere, to push for their protection. There is no green and just future anywhere without protection for our blue oceans and all who depend on them.

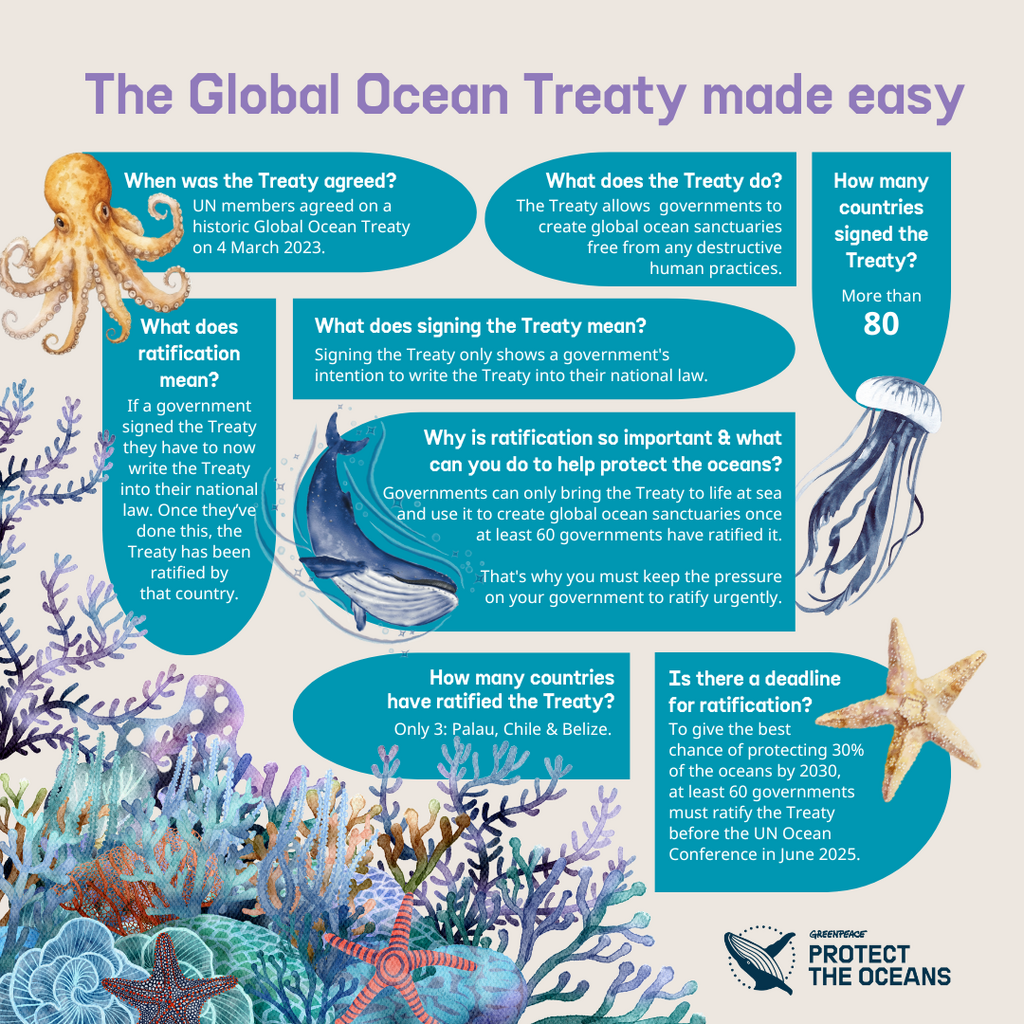

The adoption of the Global Oceans Treaty by the United Nations in June 2023 was a massive step toward ocean protection. It took decades of work from many nations and organisations and the support of millions to achieve, but there is still work to do: The Treaty is a powerful tool — which can be used to create vast ocean sanctuaries where marine life can recover and thrive — but will only enter into force once at least 60 governments have written it into their national law.

The world is watching — and waiting on — this countdown for ocean protection!

Which countries have written the Global Oceans Treaty into law?

From early ratifiers like Palau and Chile and all the way through the number 60 we’ll be tracking nations as they sign the treaty into law.

Countries to ratify: Palau, Chile, Belize, Seychelles, the European Union

Don’t see your home or resident nation included above? Add your name to our global petition to call on leaders to create new ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet:

Add your name to call on leaders to create new ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet.

Greenpeace urges governments to ratify the Treaty by the UN Ocean Conference in Nice in June 2025, and at the same time to create new marine protected areas.

From Treaty to Sanctuaries

With a heating climate, overfishing and pollution pushing our oceans to the brink of collapse, world leaders need to sign the Treaty into law to bring it into force and unlock its potential for creating ocean sanctuaries that can ensure we protect at least 30% of the oceans by 2030. Alongside ratification, governments must also start to develop the first ocean sanctuaries proposals.

In September 2023, Greenpeace International published 30×30: From Global Ocean Treaty to Protection at Sea setting out the political process to deliver protection for the global oceans.

Alongside ratification, governments must also start to develop the first ocean sanctuaries proposals. The report outlines the political steps and actions necessary to establish ocean sanctuaries using the Treaty and recommends three specific sites on the high seas to be the first set of ocean sanctuaries, due to their ecological significance: the Sargasso Sea, the Emperor Seamounts in the Northwest Pacific Ocean and the South Tasman Sea/Lord Howe Rise between Australia and New Zealand.

We’ve come so far since 2005, when Greenpeace first publicly called for a new treaty under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which would protect biodiversity and provide tools to create marine protected areas on the high seas.

The journey toward safer oceans continues, and we’ll only make it far as we go together!

Becca Field, Chris Greenberg, and Gaby Flores are Multimedia and Content Editors at Greenpeace International.

Texte intégral (1659 mots)

One of the most extraordinary experiences I’ve had as a marine biologist was when we were tracking lobsters on Wolf Island in the Galápagos Islands in 2003. The work occurred at night, so I used to take a nap after lunch. One day, I was still asleep in my pyjamas when suddenly, someone came running to tell me there was a whale shark under the boat. I thought they were joking, and tried to ignore them, but they kept insisting, and when I looked over the deck, sure enough, there it was. I was so excited that I just jumped into the water. The crew passed me a diving mask, and I spent the next 45 minutes swimming around in my pyjamas with a juvenile whale shark. I started asking myself where it had come from and where it was going. Years later, I would discover that juvenile whale sharks are actually quite rare in the Galápagos. Most whale sharks here are large adult females, and we still don’t know why!

The natural environment has always fascinated me. Initially, I wanted to become an ornithologist because I love birds. I never saw myself as a marine scientist until I was about sixteen when we went on a school trip to the north of Spain. We spent a week in Galicia doing science work on the seashore and boats, which changed everything for me. After finishing my PhD in Ocean Science in 2001, I came to the Galápagos, and I’ve been involved in research here ever since.

I joined the 2024 Greenpeace Galápagos expedition on the Arctic Sunrise to help gather information on the variety of fish and larger marine life that live in the oceans around the Galápagos Marine Reserve. The open ocean is much more vulnerable than we thought, and we need a baseline to measure change and improve the conservation of this area.

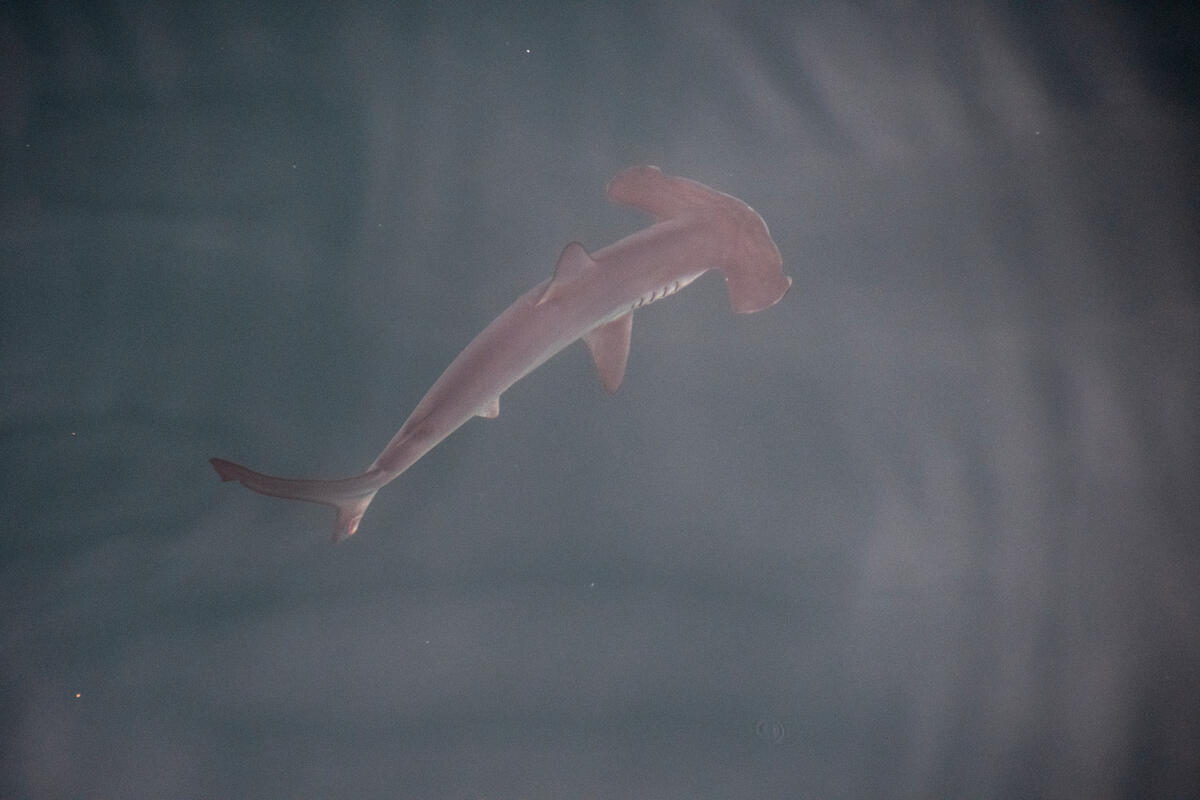

The primary goal of this expedition was to track sharks around the Galápagos Marine Reserve and understand to what extent they live inside protected waters and move out to unprotected waters. In this region, there are several endangered or critically endangered migratory species that we’re interested in, like hammerhead sharks, which move between the Galápagos Island and Cocos Island along a swimway called the Cocos Ridge.

Human activities like overfishing, poaching, or ship strikes directly impact these creatures, and there are things we can do about these dangers. By studying the populations, habitats, and migratory routes of the affected species, we can create areas to protect them.

The historic Global Ocean Treaty is a tool countries can use, but they must first ratify it as quickly as possible. The Treaty can only be brought to life once at least 60 governments have written it into their national laws.

If we’re serious about protecting 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030, political leaders must prioritise Treaty ratification or time will run out. Leaders come and go, but the ones who ratify the Treaty will leave a legacy of lasting impact for generations to come.

The oceans not only provide a home to many incredible species, but they’re also extremely important in regulating the climate. There is no green without blue. The high seas comprise over 60% of the world’s oceans, and whether we think about them or not, they are relevant to our daily lives. Oceanographers recently discovered that Galápagos can affect the climate as far away as the United Kingdom thanks to a system of currents that transports heat throughout the oceans.

We’re one little blue planet floating in the middle of a vast, cold emptiness of space. Without the oceans, there is no life on Earth; that’s why we simply cannot fail to protect them.

Alex Hearn is a Professor of Marine Biology at Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador and co-founder of the Galápagos Whale Shark Project and MigraMar.

Add your name to call on leaders to create new ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet.

Texte intégral (975 mots)

Isabela Island, Ecuador – Scientists on a Greenpeace expedition in the Galápagos Marine Reserve believe they have found what could be the first known smooth hammerhead shark nursery in the region after observing several young pups. For the first time in the Galápagos, the team was also able to track a subadult smooth hammerhead, which they named after the actress and ocean ambassador Alba Flores.

The Galápagos is famous for its aggregations of adult scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini), but the smooth hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena) is rarely observed and has never been tracked until now.[1] After several observations and documentations of juvenile smooth hammerheads in a small bay at Isabela Island, scientists now believe that this could be the first known nursery for smooth hammerheads in the archipelago.

Alex Hearn from Universidad San Francisco de Quito and MigraMar, lead scientist on the expedition, said: “This is an amazing discovery! Not only is this species rarely reported here, but in this bay we have found numerous young-of-the-year, suggesting that this might be a nursery site.”

Paola Sangolquí, Marine Coordinator at Jocotoco Conservation Foundation, said: “The Galápagos Marine Reserve never stops surprising me. This finding shows us the importance of protecting the reserve and its surrounding waters. I hope all the information collected throughout this six weeks expedition will help to make a strong case for the ratification of the high seas treaty and the protection of migratory species, who don’t know about boundaries.”

To be confirmed as a bona fide nursery site, three criteria need to be fulfilled – first, there must be more shark pups here than in surrounding areas; second, the sharks must reside at the site for extended periods of time, and third, the site must be used by successive generations of pups.

Alex Hearn said: “If we can learn why the smooth hammerhead pups use this particular location, we can make predictions about where else we might find them across the region. Here in Galapágos, the sharks are protected, but this is not the case when they, as a migratory species, leave the reserve. If we can map the sharks’ key habitats, we can take steps to push for more protected areas in the high seas, where these sharks migrate, to avoid them being caught in the first place.”

The science team were able to fit a satellite tracking device to a subadult smooth hammerhead – a female they named “Alba” after the actress and ocean conservation advocate Alba Flores, who was on board the Greenpeace ship Arctic Sunrise during its first week in the Galapágos. As the scientists track Alba the shark’s movements, they will be able to assess her vulnerability if she leaves the protected waters of the Galapágos Marine Reserve.

Alba Flores, best-known for playing Nairobi in the hit Netflix series Money Heist, said: “I am still very moved by my experience in the Galapágos. Knowing that a shark now bears my first name is a humbling thought and an important symbol for me which commits me to protecting the oceans even more. I’m determined to continue to speak out on the subject and support the people who work every day to defend this amazing wildlife.”

Sharks are key species to keep the balance in fish populations in the ocean, they help keep the food chain in the right track controlling prey populations. This prevents overgrazing and therefore biodiversity. Hammerhead sharks are also sensitive to changes in their environment, making them indicator species for the health of marine ecosystems. The shark tracking is being conducted by a team of independent scientists on board the Arctic Sunrise and the data collected during the expedition contributes to securing future ocean protection and the futures of generations of sharks in the region.[2]

Sophie Cooke, Arctic Sunrise expedition lead, Greenpeace UK, said: “Previously, it was impossible to protect this high seas area where these sharks migrate. But now, using the recently won UN Global Ocean Treaty, governments have a chance to boost protection of the migratory species in this region and provide a powerful example to the rest of the world of how to protect the high seas.”

ENDS

Photo and video footage available from the Greenpeace Media Library.

Notes:

[1] Smooth hammerhead sharks lack the characteristic cleft in the centre of their hammer-shaped head, which gives scalloped hammerhead their name, and is classed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. Hammerhead sharks are particularly vulnerable to longlining, and fishing fleets today operate just outside the borders of the reserve. In fact, the last reliable records of smooth hammerhead sharks in Galápagos came from an experimental longline fishery inside the reserve in 2004.

[2] The research expedition aims to emphasise the power of marine protection, documenting the success of the Galápagos Marine Reserve and the incredible wildlife and habitats of the sea near the Galápagos.

Contacts:

Magali Rubino, Global media lead for Greenpeace’s Protect the Oceans campaign, Greenpeace France: magali.rubino@greenpeace.org +33 7 78 41 78 78 (GMT+1)

Karina Vivanco, coordinator communicator at Galapágos Science Center, avivanco@usfq.edu.ec, +593 99 750 6617

Lire plus (470 mots)

Turin, Italy – The G7 Climate, Energy and Environment Ministers meeting has concluded with a coal phase out deadline that is too little too late and a further damaging endorsement of fossil gas.

Tracy Carty, Global Climate Politics Expert, Greenpeace International, said:

“The commitment to phase out coal is simply too little, too late. If they are serious and aligned with what the science says is needed to keep 1.5° within reach, G7 countries must ditch this dinosaur, planet-wrecking fuel no later than 2030. And the climate emergency demands they just don’t stop at coal. Fossil fuels are destroying people and planet and a commitment to rapidly phase out all fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – is urgently needed.

“Faced with climate catastrophe, the G7’s persistent endorsement of fossil gas is alarming. Gas is not needed, not cheap and is certainly not a ‘bridge fuel’ to a safe climate. The biggest fossil fuel threat today by wealthy nations is coming from the rapidly expanding LNG industry. An urgent shift is needed towards less, not more, gas – and massively expanded renewables.

“G7 Climate and Energy Ministers offered little to inspire confidence in their commitment to agree to an ambitious new climate finance goal at COP29 later this year. Given their wealth and historically high emissions, G7 countries are among those with primary responsibility for providing international financial support to developing countries for climate action. By the G7 Summit in June, leaders need to make clear they will not be heading to the COP empty handed and be ready to significantly increase support. They need look no further than taxing the fossil fuel industry and other high emitting sectors in order to generate revenues to do so.”

Irène Wabiwa, Project Manager, Greenpeace International said:

“G7 Ministers reiterated the Convention on Biological Diversity’s COP15 commitment of US$20 billion by 2025 per year of finance for biodiversity. Unfortunately, they also promoted carbon credits and offsets as key solutions to both generate money flows and protect forests. Wealthy countries such as the G7 have enough financial resources to deliver the US$20 billion to developing countries by 2025 without reverting to false solutions. Estimates show that the world is already spending US$1.9 trillion per year on subsidies to industries that are destroying nature. US$20 billion is equivalent to only 1.1% of that amount.”

ENDS

Contacts

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Follow @greenpeacepress on X/Twitter for our latest international press releases.

Lire plus (372 mots)

Ottawa, Canada – The fourth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC4) for a Global Plastics Treaty ended on a disappointing note as the negotiation caved in to the interests of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry.

Graham Forbes, Greenpeace Head of Delegation to the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations and Global Plastics Campaign Lead at Greenpeace USA, said: “The world is burning and member states are wasting time and opportunity. We saw some progress, aided by the continued efforts of states such as Rwanda, Peru, and the signatories of the Bridge to Busan declaration in pushing to reduce plastic production.[1] However, compromises were made on the outcome which disregarded plastic production cuts, further distancing us from reaching a treaty that science requires and justice demands. People are being harmed by plastic production every day, but states are listening more closely to petrochemical lobbyists than health scientists. Any child can see that we cannot solve the plastic crisis unless we stop making so much plastic. The entire world is watching, and if countries, particularly in the so-called ‘High Ambition Coalition’, don’t act between now and INC5 in Busan, the treaty they are likely to get is one that could have been written by ExxonMobil and their acolytes.

“We are heading towards disaster and with time running out – we need a Global Plastics Treaty that cuts plastic production and ends single-use plastic. There is no time to waste on approaches that will not solve the problem.”

ENDS

Notes:

Photos and videos are available from the Greenpeace Media Library.

[1] Bridge to Busan: Declaration on Primary Plastic Polymers

Contacts:

Angelica Carballo Pago, Global Plastics Campaign Media Lead, Greenpeace USA, angelica.pago@greenpeace.org , +63 917 1124492 (also in Ottawa, Canada)

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Follow @greenpeacepress on X/Twitter for our latest international press releases.

Lire plus (207 mots)

Milan, Italy – In an interview with CNBC today[1], Andrew Bowie MP, Minister in the UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, made a statement that the G7 has agreed to phase out coal during the first half of the 2030s.

In response, Tracy Carty, Global Climate Politics Expert, Greenpeace International, said “The G7 phasing out coal in the first half of the 2030s would be too little, too late. If they are serious and aligned with what the science says is needed to keep 1.5° within reach, G7 countries must ditch this dinosaur, planet-wrecking fuel no later than 2030 – and as the climate emergency demands they can’t just stop at coal: Fossil fuels are destroying people and planet and a commitment to rapidly phase out all fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – is urgently needed.”

ENDS

Notes:

[1] Shared in an interview to CNBC

The G7 Climate, Energy and Environment Ministers Communique is expected to be published on 30 April, 2024.

Contacts:

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Texte intégral (980 mots)

Letter from a concerned father to Ramy Mohamed Youssef, Chair of the UN Tax Convention Committee, so he ensures the world gets a new fair global tax system. The historic vote to grow the UN’s role in international tax is a golden opportunity for more inclusive decision-making and fairer taxation for all nations.

Dear Mr. Ramy Mohamed Youssef,

As the Chair of the UN Tax Convention Committee, you have the power to create history this year.

I’m writing to you as a dad, a concerned citizen and a taxpayer. Today I feel angry and afraid, since I’m witnessing the collapse of everything that’s important to us: from peace to essential ecosystems. How is this possible?

We both know that this is mostly because multinational corporations have been exploiting the majority of the world for way too long, and governments in some rich countries have facilitated it. They’re making billions on the destruction of the world and our suffering. And then, they hide their profits in tax havens. A downward spiral where wealth and power have become so concentrated as to threaten democracy, civilisation and the living world we’re part of.

I come from Africa, an incredibly rich continent where wealth doesn’t stay. How can I explain this to my kids? I could tell them that this is because of the way the economy is set up. A system that enables plundering, exploitation and around US$480 billion that are lost to tax havens each year, instead of funding what is really essential.

I could also tell my kids that humanity has all the money, knowledge and technology we need to thrive. So it is in humanity’s hands to prioritize the wellbeing of people and the planet. Especially now, when access to basic standard of living, health, education and social security is getting more and more difficult, as the planet heats and extreme weather events become more frequent, putting us and all living things at risk.

Mr. Youssef, you have a big responsibility and a unique opportunity to turn things around this year. Civil society, academics and countries that represent 80% of the world’s population are backing you and your colleagues at the UN Tax Convention Committee to change the global tax rules, which are critical for how the global economy works. The money for everyone’s basic needs and the recovery of climate and nature is there. Now we need equality, transparency and accountability. Polluters must pay and the wealthy must be taxed fairly.

It’s time for bravery, powershift and new economic thinking to build a shared wellbeing. We need you Mr Ramy Youssef to stand up to those who’ve taken from us and for those who are suffering the consequences, by making sure that the world gets a new and fair international tax system. We’re counting on you to make a leap towards the future we’re all longing for.

Sharing this letter is within my power. I trust you will do all in yours too.

Fred Njehu, Pan African Political Strategist, Greenpeace Africa

We’re asking governments to put wellbeing at the top of the agenda. Join our global movement and let’s demand wellbeing for all!

Texte intégral (6486 mots)

Hannah Stitfall’s been getting updates from onboard the Arctic Sunrise, one of Greenpeace’s research ships, since the beginning of the series, from Panama where it set sail out into the Galápagos Islands marine reserve.

We heard as it crossed the equator, and we’ve learnt about the pioneering research the scientists and volunteers have already done on seamounts in the area. And now, they’ve finally anchored and we’re joining them onboard for an episode all about Galápagos.

You’ll meet Sophie Cooke the expedition lead; Captain Mike, the man behind the wheel; Andrea Vera, an Ecuadorian scientist; and Hannah is lucky enough to be able to catch up with Spanish actress Alba Flores (from Netflix’s Money Heist), who’s just got back home after spending a week onboard.

Presented by wildlife filmmaker, zoologist and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall, Oceans: Life Under Water is podcast from Greenpeace UK all about the oceans and the mind-blowing life within them.

Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music or wherever you get your podcasts.

Below is a transcript from this episode. It has not been fully edited for grammar, punctuation or spelling.

Usnea (Intro):

Hello, my name is Usnea and we are currently on our ship the Arctic Sunrise in the Galápagos Islands.

Hannah Stitfall:

We’ve been tracking the voyage of the Arctic Sunrise since the beginning of this series from Panama where it set sail, out into the Pacific Ocean. We were listening when it crossed the equator.

Usnea (Intro):

Really, really, really special and a beautiful thing to be a part of. And so we crossed last night at 01:30 in the morning.

Hannah Stitfall:

And we’ve heard about the pioneering research they’ve already done on sea mounts in the waters there.

Andrea Vera (Intro):

This is what sets the migratory route for some critically endangered species.

Hannah Stitfall:

But Usnea is far from the only person on the ship. They’re about 30 people, scientists, volunteers, first mates, cooks, cameraman, comms people; all crucial in gathering the research and sharing it with the outside world.

I’m Hannah Stitfall. And today, we’re joining them on board, ben episode all about the Galápagos.

Sophie Cooke (Intro):

It’s been absolutely amazing to see the richness and diversity of marine life here. Every time you go out on deck, you see something.

Hannah Stitfall:

This is Oceans: Life Under Water, Episode 10.

Usnea:

Here we are on board the Arctic Sunrise. And our plan is to walk around the ship and meet some of the amazing people that work here.

Hannah Stitfall:

The first person you’re going to meet is Sophie Cook. Sophie’s a Greenpeace campaigner and is the leader of this particular expedition. She and Usnea got chatting about how the expedition came about.

Usnea:

So I have the pleasure of being here with Sophie Cook, who is our expedition lead for this awesome adventure we’re on. Sophie, can you tell us a bit about why we are in the Galápagos? What are we doing here?

Sophie Cooke:

A year ago, we won the global ocean treaty. And as part of that we wanted to show people what ocean protection can be. And what is more iconic and well known globally from marine reserves than here at this amazing, amazing place that Galápagos Islands. And it has totally been that. The things that we have seen and the species and just the amount of life in the water has been absolutely, overwhelmingly wonderful.

Usnea:

And Sophie Can you tell us a bit about the work that we’re digging into here?

Sophie Cooke:

On the way here we came through the high seas and visited to sea mounts. And so these are underwater volcanoes that can be aeons old but they haven’t reached the surface. And sea mounts are really important biodiversity hotspots, especially for far from land. Migratory species use these as stepping stones between the areas of land even when you’re going 1000s of miles across the ocean. These are like the navigation waypoints, which is very cool. And so we took environmental eDNA samples, and so that’s like tiny bits of skin and faeces that animals drop, we can pick that up in the water and use that information to know what’s come by. And then we’ve also been using the BRUVs, which are baited underwater cameras that we put in the water at two hours at a time and see which species are attracted there. There were blue sharks out at the remote seamounts in the high seas, showing that they’re using these waypoints to the land. There is a really key sea mount here, that’s an oceanic seamount called paramount. And all the way on the way here where we were looking for thresher sharks and hadn’t seen them. And we saw them at paramount, which was really fantastic and very exciting for a lot of people on board.

Usnea:

Can you tell us a bit about the shark tagging and why we’re so excited and involved in this.

Sophie Cooke:

We are working with Dr. Alex Hearn and his team. And they have been tagging sharks in this region for 20 years. And their work was a significant direct part of a brand new marine reserve within the Galápagos economic exclusion zone. So the 200 miles around Galápagos, there was an extra new reserve two years ago that 60,000 square kilometres, so it’s absolutely massive and that has, half of it is no fishing at all. And then the other half is no long lines, which are the biggest threat to sharks. So we are helping continue that work. The more understanding we have of these migratory species, the more we can understand where to focus protection on.

Usnea:

We are currently drifting not too far away from the Arctic Sunrise over a sea mount and have just put in some lures. It’s a hopeful plan this morning.

Sophie Cooke:

At first things were really slow. We haven’t tagged as many sharks as we expected to. But we instead have found an exciting new discovery that we weren’t expecting. And that is the bay that we were anchoring in for the second week to do this work. We were seeing these juvenile, smooth hammerheads. There have been a few sightings in the Galápagos, but really no substantial evidence that they were here.

Crew member:

Shark on board. We’ve got a total length… (speaking Spanish)

Sophie Cooke:

…And because we’re finding juveniles, it looks like are they using that area as a nursery?

Crew member:

Oh, yeah. Okay, got it. Okay.

Usnea:

So we if we zoom out to look at oceans globally, what is the current situation right now in terms of protections.

Sophie Cooke:

Looking at the high seas, so this is the areas beyond 200 miles from any land, there is so little protection out there. There are a few designated marine protected areas. Some of them are in Antarctica. There’s some in the North Atlantic, but those are very much paper parks. I’ve been in, in a large MPA in the North Atlantic, with industrial fishing vessels, pulling sharks out of the ocean, you know, these should have real protection, these marine protected areas, these MPAs, they should be protecting these places from industrial fishing. We can’t be calling a place protected when their seas can still be stripped of all their life. So now we have this perfect opportunity where we can protect these places. We’ve got the global ocean treaty, we need to put pressure on them to make sure that fishing, industrial fishing, deep sea mining are all parts of these protections there and that we have real marine protected areas out there.

Hannah Stitfall:

The next person you’ll meet is Ecuadorian scientist Andrea Vera. Usnea had a chat with her during a shark tracking expedition to hear more about why the Galápagos Islands are such a unique place ecologically.

Andrea Vera:

My name is Andrea Vera. I’m from Ecuador. I’m 25 years old. And I’m currently working with an NGO called Miramar which is a network of scientific researchers in the marine area. And we study older, mainly migratory species along the eastern tropical Pacific to try to make different conservation actions along this area.

Usnea:

Can you tell us a little bit about what makes this place so special? And your connection to it?

Andrea Vera:

What I particularly love about Galápagos is that right when you arrive here, we’ll see these amazing volcanic rock However, it’s also like, surrounded by ocean. So there are places for instance, in Isabela or in north where you’re going to see a volcanic rock, you’re going to see a penguin, a cactus, and you have the ocean. So it’s a pretty like unique environment. Will you have these amazing diversity of species from sharks, marine mammals, reptiles, birds, in the particular thing is that it’s an island, we have so many species that are endemic to the area. So you are not going to see these species anywhere else rather than just here in the Galápagos.

Usnea:

Andrea, can you perhaps highlight some of the most like iconic endemic species here?

Andrea Vera:

Yeah, for sure. Well, you can see the marine iguanas, which are pretty unique. There are no other marine iguanas that feed from algae. And also we have the penguins, the Galápagos penguins, which they’re actually the second smallest penguins from all the penguins, that’s really cool. We also have the Galápagos sea lions. Let’s not forget about the Galápagos sharks, just like from here. While also another like unique and pretty amazing species that we can find here; the hammerheads, whale sharks. Yeah, and lots of seabirds. Some of them are also endemic from here.

Usnea:

And we’re here shark tagging, like what is so unique about this species? What’s so special about these sharks here in Galápagos?

Andrea Vera:

Well, the most important thing about sharks in Galápagos is that we have lots of them and different species of them. So mainly sharks, they come here to the Galápagos to reproduce to feed also to grow. And some of them even not, like have babies here in the Galápagos. And so it’s an oceanic Island. It’s one of the like, the main points where that these highly migratory sharks come in throughout their way. So we have that like this really, really interesting like migratory pathway here in the Pacific. And Galápagos is one of the hot spots for this species, yes.

Usnea:

And, Andrea, can you share with us your role in this expedition that we’re currently on?

Andrea Vera:

Yeah, sure. So with my working partner Daniel, we’re in charge of carrying out the BRUVs, which are baited remote underwater video systems. So basically, is like imagine our triangle with two GoPro cameras in the sides, and we have some bait in the middle. So the idea is try to capture the different species that are around the area and that are attracted to the bait in these like 10 metre from the surface to the bottom of the ocean. So we probably will try to see if we’ve confined and we can see like different species of sharks for instance, we have actually seen some silkies, some hammerheads, some tuna we have also seen and other species of fish, which has been really interesting. So we try to describe the biodiversity and also like characterise the areas, for instance how many sharks do we see how many individuals of one especially do we see in each area. Today, my main job is to be like the logger. So I’m going to be taking notes about like the time, know which species it is, the sex, we’re gonna take some measurements like the total length, the fin length, the girth. And also take this measurement about like the latitude longitude, and the tag ID.

Usnea:

And what is your favourite ocean animal.

Andrea Vera:

My favourite definitely has to be the whale shark. Like the first time we get to swim with one. They’re like a particular animal because even though they are sharks, they have like this like charismatic look like their eyes. They’re like mammals, they’re like really warm. And I don’t know, like, you just want to hug them. I don’t know, they’re really interesting. And I really love the fact that this parts they have in their body they’re like, or fingerprints that they are unique from each individual. And there are a lot of like mysteries and things that we don’t know about them that makes them amazingly mysterious.

Usnea:

We’ve talked a bit about what’s so awesome about the Galápagos and special here. Can you tell us about some of the threats Galápagos, and its species, endemic and not, are facing here?

Andrea Vera:

Well, one of them main threats, I would say would be the plastics. If you can see there are parts of Galápagos that people never get there. However, you end up watching a lot of trash in actually, during our expedition here in open ocean, I’ve seen some plastic bottles in the ocean, some plastic garbage and everything. And the thing about this is that, well, plastics, they’re like a cocktail party, they actually call them. So when they get to the water, they dissolve. And they start like, well, they don’t dissolve, they’re start to break up into microplastics. And it’s microplastics. And they actually capture all this, like toxins, like PVCs and everything that is in the water, and was when a small fish, they eat them. And then larger fish like sharks, they eat this smaller fish, they buy or accumulate these plastics.

Also, there’s another really big threat, which is climate change. We have seen it and we were in this eastern part of the Galápagos, the water was really warm. So just imagine sharks, they don’t like this really hot water. So they will have to change their like migratory routes or their like their distribution, to allocate to better places that are cooler for them to survive. There’s the saying that I really love when they were trying to explain me like why should we protect the way that for instance, hammerheads go from the Cocos Island to the Galápagos Island. They are protected in Cocos Island and as well hear in Galápagos Island, but what happens along their way is like your kids in a bus, you protect them that you know that they are safe your house, you know that they are safe in school, but what happens if you don’t know if they’re safe the bus? Okay, so we’re trying to, to save them along this way. We’re trying to give them like these protected areas where they can move from one place to another that we know that they’re really important places for them. It doesn’t make sense protecting them in one place and another and that they can be fished in the middle of it.

Usnea:

What role does research expeditions like this play in conservation efforts? And do you think that science can really make a difference?

Andrea Vera:

Well, I’m gonna answer from back to the top. So yes, I really believe that science can make a difference, in conservation. Science can become actions. So understanding where species are, what they do and the main places that some species reproduce, you can know these really important places for the lifespan of the species that must be protected. So with this you can go to politicians and create laws in changes that can improve conservation of those species.

Hannah Stitfall:

There was huge excitement when Spanish actress and star from the Netflix series Money Heist, Alba Flores, joined the Galápagos expedition for a week. Alba is one of Greenpeace’s Ocean Ambassadors. In recent weeks, she was invited by Greenpeace to join the Galápagos expedition for a week, I was lucky enough to be able to catch up with her once she got back home.

Alba Flores:

Hello! How are you?

Hannah Stitfall:

I’m very well! How are you?

Alba Flores:

I’m good. I’m good. I’m still dealing with some jet lag. But I’m really good. Yeah. Happy.

Hannah Stitfall:

So Alba, you joined the Galápagos expedition very recently. How long were you on the ship for and what were you doing there?

Alba Flores:

I were with them for a week. And we were doing all these videos on the campaign about the marine sanctuary that they have there. And we also were like, as a witness of the work that the scientists were doing there.

Hannah Stitfall:

And can you describe for us what it was like being on the boat? I mean, did did you have any expectations before you went?

Alba Flores:

I never went on a ship in such a long journey. I never sleep over over a ship. So I didn’t know what to expect, because it was the first time for me. And it was like comfortable experience. Like they know how to make you feel that you’re at home.

Hannah Stitfall:

What would you say your favourite part of the experience was.

Alba Flores:

Well the snorkelling was awesome. I wish we could like swim more in those waters in that part of the ocean because it is full of life. And, and I also enjoyed the time spent with a crew because they are like, full of stories about activism and sea adventures and things like that. And that was like, I learned a lot. Everyone was in bed at like nine. Because they work really, really hard. I mean, all the crew, they are amazing. They were so helpful with the scientist and with us, with the media. And sometimes we asked for impossible things like, can you turn all the ship, because the sun, you know, is is too hard, and we cannot shoot this properly. They are like, kind of like super heroes and super heroines.

Hannah Stitfall:

And the Galápagos marine reserve is one of the best examples of ocean protection in action. It’s got, what 200,000 square kilometres are protected. What does that look like? And how different is it to unprotected areas?

Alba Flores:

Well, I never went to unprotected areas, but in the park, you have protected areas. And inside those areas, are there high protected areas. And you can also see the difference between them like…

Hannah Stitfall:

Can you? Just between the protected areas and the highly protected areas, you can clearly see a difference?

Alba Flores:

Yeah, of course, because the highly, highly protected areas. No human have been there, at all. So in those parts are aware, the you know, all the creatures, all the animals is where they are. They’re really, really safe to give birth and everything. So we didn’t see any ship or boat, or people for two or three days do it was like

Hannah Stitfall:

Wow!

Alba Flores:

Nobody was there. So, in Galápagos, we were not allowed to scuba diving. Because it’s protected. We just could do a snorkelling but doesn’t need like anything else there because because life is pumping up to your face like you just gotta go like this into the water. And its like… Woah! Because it’s like: a shark, a manta ray, a penguin like this in the same like two metres square.

Hannah Stitfall:

Wow!

Alba Flores:

Yeah, really awesome.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh, I bet it’s… I visited marine protected areas before but I’ve never, I’ve never been to anywhere that’s highly, highly protected. As somebody that loves wildlife, but that must have been such an experience for you. Oh, I’m jealous, very jealous.

Alba Flores:

Yeah, I mean, I’m so lucky. So, so lucky. It is overwhelming. Just being in a ship, I think is really, really overwhelming because you have a sense of hugeness never ending space. And I’m just another animal between all these creatures. I think that is a lesson of humility, oceans are crucial. And all scientists, all thinkers of the people that knows about this, that have been studying this, they keep on saying it, like, this planet, the blue planet, is blue for a reason, like we are like, mostly water, we have to protect the oceans. And in that way, the oceans will protect us.

Hannah Stitfall:

But I think now, so many more people are aware and interested in issues with the environment and ocean conservation. And of course, having someone like you that’s actively going out to these places, and you’re and you’re vocal about it to your followers. You know, it’s it’s really important, because you might be reaching people that have never really thought about ocean conservation before but they watch you for for the shows you’re in, you know, so you’re doing a really, really good job as well to be a part of it. You know?

Alba Flores:

I hope so. I mean, that’s the point of doing. I don’t have a way to measure how well this is working like to spread a message that I believe in, and that the people who is I don’t know watching my my work, like my TV shows and everything if they engage with a message, but I have to fight for what I believe.

Hannah Stitfall:

Well I think just keep going because we think you’re doing a fantastic job. And I just want to say a huge thank you for coming on and talking to me today. It’s been an absolute pleasure and really do keep up the fantastic work.

Alba Flores:

Thank you.

Hannah Stitfall:

the Arctic Sunrise is a big icebreaker, a 50 metre long ship designed for polar expeditions coming in at almost 1000 tonnes. The scientists and the team of volunteers are one thing. But who’s the crew keeping the ship going? Let’s meet the Captain.

Captain Mike:

My name is Captain Mike. And I’m one of the Greenpeace captains currently on the Arctic Sunrise.

Usnea:

Would you tell us a little bit about how the journey has gone so far?

Captain Mike:

This expedition is just gone from strength to strength. The beginning was the tranquil seas of the mid international waters between Galápagos and Ecuador. Because it took a lot of to prepare the ship for for the Galápagos, a tremendous amount of biohazard control that we needed to make sure that the ship was completely clean of any foreign bugs, and how it was cleaned and made sure we didn’t have certain seeds and certain fruits and certain things on board that we could bring into the island that could evolve into their own super beings. So we had to do all of these controls before we arrived. So I had a little bit of apprehension, whether they would even let us in. Fortunately when we did arrive, and we’ve done such even like blanking out all white lights, only yellow light is visible from the ship. So it doesn’t distract birds or anything. When we did come there did a vigorous inspection. And once we got that certificate signed off, and yes, we had passed and we had a licence to navigate the Galápagos archipelago. The relief was phenomenal. And then the adventure really started.

Usnea:

Can you tell us a bit about what your job as Captain means and looks like on a day to day basis.

Captain Mike:

On a day to day basis. I would liken myself probably to mother hen with a clutch of chicks that are all running about.

Crew member:

Seven o’clock, seven o’clock. Copy.

Captain Mike:

have an engineering department very technical in keeping the ship running. I have a deck department that is responsible for the maintenance and the operations of the decks.

Crew member:

For day eight o’clock…

Captain Mike:

Then I have a galley, and that’s all the food and that’s quite a demanding a department because there’s a lot of hungry mouths to feed. There’s 36 people on board when it’s on its full capacity and we’ve been up to that on this trip. And then we have the the navigational side as well.

Crew member:

And then we’ll stop and drift back through the night and be back in position…

Captain Mike:

Having all of these personalities and activities going on.

Crew member:

Thank you 1891

Captain Mike:

I do feel a big part of mine is trying to encompass and make sure everybody’s comfortable and feeling safe and feeling that they can be at home on board the boat.

Usnea:

What’s it like to be a ship captain, on a boat like this that’s conducting such important research.

Captain Mike:

For me to be here in the Galápagos system is a complete honour. And I think the the rest of the crew recognise that too. Boats don’t come in and out of the Galápagos boats that operate in the area stay in the area, we are an international vessel coming in and out. And I describe how complicated and complex that is.

So to be on a boat that can come in, this is an international mariners dream to be able to navigate these waters. But not only that, we’re not just navigating on our own here, we have the best guides who give us their first hand experience. And that is years of experience. They’ll tell us all the detail, the extreme detail or everything. So for me, I have been at sea for nearly 40 years. But I’ve never seen a system or an archipelago as beautiful and as imaginative as this is, it is just mind boggling. It’s creative, it’s just breathtaking, and has really inspired me to carry on.

I do have this want to make the planet beautiful, to help the planet stay beautiful, it is already beautiful. And I wanted to stay intact. And hopefully even future generations will have that possibility to see that diversity and that we can hold on to that as much as possible. So that’s what keeps me going. That’s what drives me do what I do.

Captain Mike:

Copy that Pumar, done with the diving and you’re returning to the boat. We’ll turn and make a leave for you.

Usnea:

Do you feel that you’ve seen anything on this trip that’s shown us the impact of climate change on the oceans.

Captain Mike:

I have seen, I have noticed that the temperatures are quite warm. Being a mariner I studied oceanography at in the Maritime College. And there is this vertical movement of water in the oceans, which on the West Coasts causes an upwelling and cold water. That’s why the fisheries is generally much richer on this side. And so I would have expected to have pockets at least of cold water, possibly 20 degrees or even chillier than that. I grew up in South Africa on the west coast near Cape Town. And we have the same effect there as you would here. But if you look here at the Aqua graph where we have our sensor, its showing us currently sort of 26 and a half degrees, so it’s phenomenally warm. Whether that’s El Nino, which it could be or climate affecting anything, but it is unseasonably warm water for the area.

Usnea:

We did have an incident with a sea turtle and some crew members. Did you want to share about that Mike?

Captain Mike:

Oh, yeah, we would just pick you picking up the BRUVs, these basic remote underwater video systems. And as we just come to the end of the line, and we had a boat, we just happen to have a boat in the water. And I think it was the Chief Mate saw, I saw, he said there’s some plastic floating. If you’ve got a boat in the water, we’ll just shoot off and pick the plastic up. But when the boat arrived at the plastic, the plastic actually was moving. And it was a it was a sea turtle caught up in plastic but it didn’t have the plastic only wrapped around its neck, apparently it had ingested into too. And they managed to be the first responders really and pull the plastic out and happy little turtle did swim away. Very thankful.

Usnea:

Beautiful. Yeah, and I remember just the look on Chris and Audrey is our Third Mate and deckhands faces as they returned. They were so impacted by being able to participate in that rescue. Like you could tell they were wildly moved by it for sure.

Captain Mike:

Things like that are life changing. I mean, I remember just freeing in plastic a bird off the west coast of Africa. Many do, a lot of gannets and they will have plastic caught on their beaks because they dive at a bright spark and it’s actually from the fishing industry and then they suddenly got a piece of rope strapped to their beak for the, until… well you see them flying. We actually called them the ‘plastic gannets’. But one was really entangled and landed on the deck and I managed to throw net over it, it wasn’t a very happy, it was really an angry bird. It didn’t, wasn’t happy with us. But I did manage to free it from the plastic and see it fly off. Moments like that are so rewarding. But I wasn’t only rewarded by feeling wise, that evening, tucked under the pillow in my cabin, was a little note from the bird. And it said Thank you, the Angry Bird.

Usnea:

Love it. It seems like it got over its feelings of anger and moved to gratitude.

Captain Mike:

I don’t think it was from the bird, but I don’t know who it was from.

Hannah Stitfall:

And now back to Sophie, the expedition lead.

Sophie Cooke:

It’s been absolutely amazing to see the richness and diversity of marine life here, it’s just been, every time you go out on deck, you see something, whether it’s the sharks swimming by, the rays leaping out of the ocean, its amazing variety of bird life. It really is quite a special place. And knowing that there were really good protections in place around the Galápagos is really wonderful. But once you start going a bit further, we still have those threats from industrial fisheries, and you get out to the high seas and these areas could potentially be mined in the future for deep sea mining. Everything is still vulnerable, where we haven’t got protections in place. So yeah, that’s kind of going to be some of the next steps is looking at where in the high seas are the best areas and that we could actually make a difference.

Our oceans are such a special wondrous place. And often the things that are happening to them we don’t see, whether it’s the industrial fishing fleet so far from land or the mining machines down on the bottom of the ocean. A lot of this is like literally like swept under the carpet we don’t realise what effect we are having here. Because it’s just so far from where our eyes are seeing every day. And so just getting over the urgency and the threats that we’re facing right now and understanding that this has to happen. Now we’ve got the treaty we need to get these places protected before we lose them for good.

Hannah Stitfall:

Next week, I’m looking more into how the oceans are changing. I’m joined by the DJ and environmental toxicologist Jayda G to talk about a little magic thing called Blue Carbon. And Amit Sharma, a scientist and climate advocate from Mauritius to understand what the changing oceans mean for the future of our island nations.

This episode was brought to you by Greenpeace and Crowd Network. It’s hosted by me, wildlife filmmaker and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall. It is produced by Anastasia Auffenberg, and our executive producer Steve Jones. The music we use is from our partners BMG Production Music. Archive courtesy of Greenpeace. The team at Crowd Network is Catalina Nogueira, Archie Built Cliff, George Sampson and Robert Wallace. The team at Greenpeace is James Hansen, Flora Hevesi, Alex Yallop, Janae Mayer and Alice Lloyd Hunter. Thanks for listening and see you next week. Transcribed by https://otter.ai

We need a global moratorium to stop the launch of this destructive new extractive industry. Join the Campaign now.

Lire plus (204 mots)

Today, Resolute Forest Products, Greenpeace, Inc., Greenpeace Fund, Inc., and Greenpeace International announced that they have resolved Resolute Forest Products, Inc. et al. v. Greenpeace International et al., No. 3:17-cv-02824-JST (N.D. Cal. 2016). Resolute Forest Products and Greenpeace Canada also announced that they have resolved Resolute Forest Products, Inc. et al. v. Greenpeace Canada et al. (Ontario Superior Court of Justice). All parties are pleased that they have turned the page on these long-running litigations. The Greenpeace parties have no knowledge of illegal operations in off-limit areas by Resolute. Greenpeace, Inc., Greenpeace International and Greenpeace Canada state that their criticism was always directed at Resolute’s legal operations in certain forests that Greenpeace believes require more protection. Greenpeace states that it will continue to advocate for protection of the environment. Resolute states that it is committed to the sustainability of the boreal forest and prosperity of its communities. Resolute and Greenpeace agree everyone should be part of this discussion and to raise concerns with each other in an attempt to resolve factual disagreements.

ENDS

Contacts:

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Reporterre

Bon Pote

Actu-Environnement

Amis de la Terre

Aspas

Biodiversité-sous-nos-pieds

Bloom

Canopée

Décroissance (la)

Deep Green Resistance

Déroute des routes

Faîte et Racines

Fracas

France Nature Environnement AR-A

Greenpeace Fr

JNE

La Relève et la Peste

La Terre

Le Sauvage

Limite

Low-Tech Mag.

Motus & Langue pendue

Mountain Wilderness

Negawatt

Observatoire de l'Anthropocène

Présages

Terrestres

Reclaim Finance

Réseau Action Climat

Résilience Montagne

SOS Forêt France

Stop Croisières