Texte intégral (795 mots)

Killed by cardboard: How old-growth forests in Sweden end up as boxes for global e-commerce

When insufficient nature protection and political inaction allows the Swedish forest industry to turn old-growth forests into cardboard and other throwaway products, it is up to us to put an end to these “nature crimes”.

As in many parts of the world, the current protection of critical ecosystems on the European continent is completely inadequate to tackle the climate crisis and the collapse of biodiversity. Despite the EU’s self-proclaimed role in protecting nature, the destruction of our oldest and most valuable forests continues on a daily basis. That’s why Greenpeace has exposed and published investigations from several countries to remind us of the urgent need to stop the destruction of nature.

In Sweden, where our latest investigation has been carried out, protecting forests is not just crucial for climate and biodiversity reasons, it’s also key for Europe’s only recognised Indigenous People, the Sámi. However, insufficient governance and self-regulation of the Swedish forest industry has resulted in vital old forests being destroyed rather than protected, the report shows. What fuels this destruction is to a big extent the demand for throwaway products like cardboard and pulp, especially from the e-commerce sector.

The Swedish investigation

- Over the course of a year, Greenpeace Sweden carried out field investigations in old-growth forests that have been destroyed. More than 60 logging sites were visited across the country. To establish transparency in the chain of custody, Greenpeace Sweden monitored the timber from clearcuts to pulp mills, either by following timber trucks or by using electronic tracking devices. 9 pulp-and-paper mills, operated by 6 different companies, including such well known names as Smurfit Kappa, SCA and Billerud, were connected to the investigations.

- By analysing statements made on company websites and seeking information in social media posts or presentations made in industry fora and such, Greenpeace Sweden was successful in establishing links between the pulp mills in question and companies that source material from them. The results show that over a hundred companies are at risk of receiving material that originated in unsustainably logged forests of Sweden. Each of these companies have been offered an opportunity to confirm or correct our findings.

- Among the companies listed in the report are giants from the e-commerce sector like Zalando, Amazon and HelloFresh. Online shopping is booming, with the e-commerce sector being a major user of cardboard to package and ship their products. According to the Swedish Forest Industries, in 2022, more than 60 percent of all timber in Sweden was turned into paper products. Therefore, it is important that companies from the e-commerce sector act.

- The report is designed to inform consumer companies of the risk that their supply chain is exposed to, and to offer suggestions for steps that they can take in order to eliminate it by

- Cleaning up their supply chain from old-growth forest material

- Actively supporting stronger EU nature-protection regulation in order to avoid such critical issues in the future

- Working towards eliminating the use of single-use packaging

Download Greenpeace Sweden’s full report:

It is time to stop crimes against the ecosystems that protect us. Strong laws and strict controls must be put in place.

Texte intégral (8195 mots)

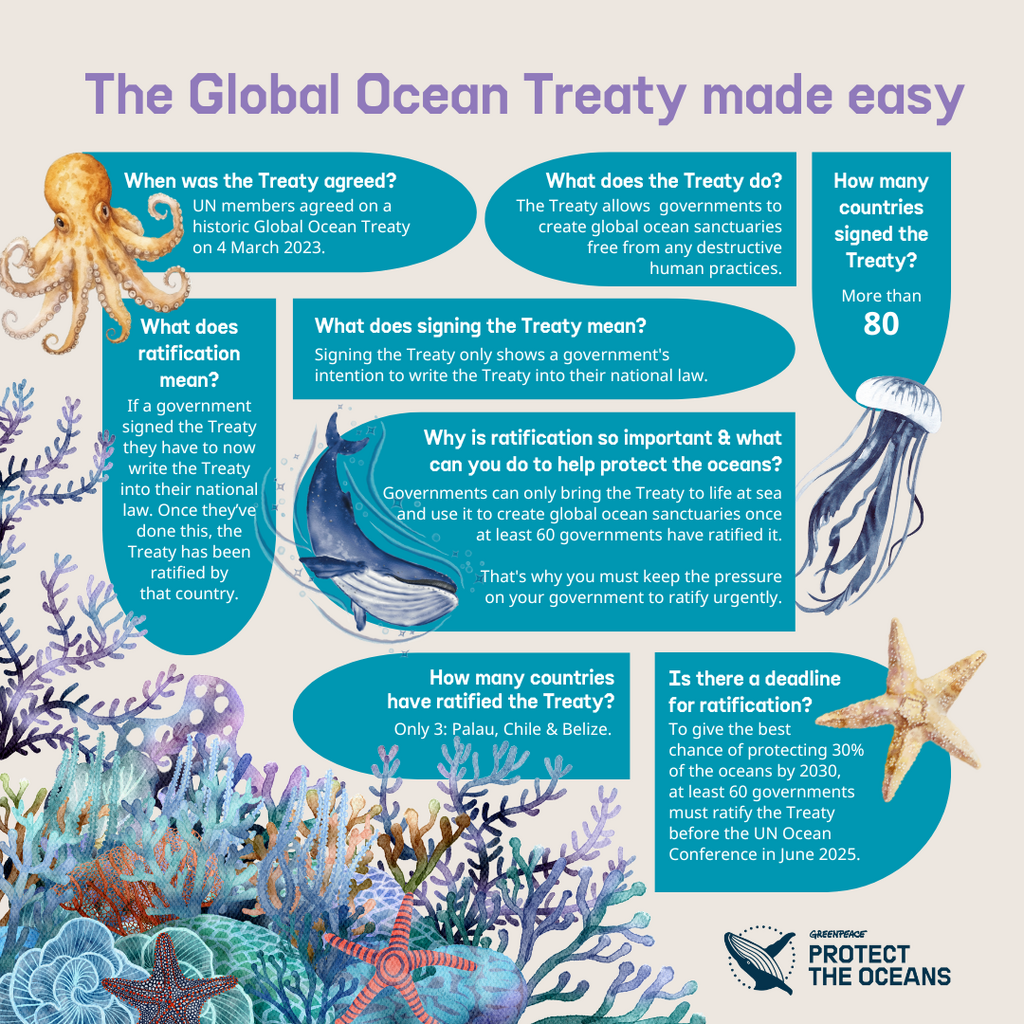

In this final episode, we’re looking to the future. The Oceans Treaty which was finally passed last year after decades of negotiations was momentous – but what actually is it? And will it do anything? Senior Policy Advisor Lisa Speer was at the UN HQ in New York when the announcement was made, and joins Hannah Stitfall to break down what it means, why it’s exciting – and what obstacles still stand in the way.

Presented by wildlife filmmaker, zoologist and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall, Oceans: Life Under Water is podcast from Greenpeace UK all about the oceans and the mind-blowing life within them.

Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music or wherever you get your podcasts.

Below is a transcript from this episode. It has not been fully edited for grammar, punctuation or spelling.

Lisa Speer:

I have been working on ocean policy for three and a half decades. And I have to say that the passage of the oceans treaty is perhaps the high point of my career, sitting in that room or standing in that room that day, that morning, after having been up for 36 hours, when the negotiators came back into the room and announced they had reached agreement, everyone got to their feet, started yelling, clapping, crying, it was an incredibly emotional moment for all of us, because we had worked together for so many years to get this thing done. And it really is one of those achievements that I think will transform how we care for our ocean and to be there at that moment was such an incredible privilege.

Hannah Stitfall:

You’re listening to Oceans: Life Under Water. I’m Hannah Stitfall. And in this final episode, I’m looking forward to the Global Oceans Treaty, which was passed last year was huge. It was the first time that nations around the world agreed that something had to be done to protect the seas, they set the 30 by 30, aim to protect 30% of the oceans by 2030. We don’t have the time to think small, like now we have time to really think big, we really wanted to do something that was not rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, but that could really achieve transformative change in the ocean.

Hannah Stitfall:

But what does that actually mean? And will it change anything?

There’s just this profound lack of observation capability that we have. So enforcement is a challenge.

Why are we not looking at 100% of the oceans to be given that kind of consideration?

Hannah Stitfall:

This is Oceans: Life Under Water, Episode 12.

My first guest is someone who is on the front line of the Oceans Treaty negotiations for nearly 20 years. Lisa Speer is a marine scientists and senior policy analyst. She was right there in the room at the UN headquarters when the treaty was finally agreed last year. And she’s joining me now from New York. Hello, Lisa!

Lisa Speer:

Hello, Hannah.

Hannah Stitfall:

How are you?

Lisa Speer:

Good. How are you doing?

Hannah Stitfall:

Very good. Thank you so much for being here today. Really appreciate it. So talk to me a bit about the oceans treaty. I mean, how long were you working on it? When did it start?

Lisa Speer:

This was a very long process. I’ll tell you. We started actually talking about the need for a conservation biodiversity treaty for this part of the ocean back in 2006. It’s been a long road. But we’re finally there. And it’s a huge step forward for the world’s ocean Cillizza.

Hannah Stitfall:

Let’s go back to basics. So what is the Oceans Treaty? What does it mean, and why is it exciting?

Lisa Speer:

So the Oceans Treaty is an international agreement that will dictate how we manage the ocean beyond national jurisdiction. And that’s the part of the ocean that is some begins, in most cases that about 200 miles from the shore and extends out from there. This vast area of the ocean has been very poorly controlled and regulated for centuries. And as a result, it is increasingly vulnerable to damaging human activities, like overfishing, destructive fishing practices, pollution, shipping activities, et cetera. And so this treaty attempts to address the and update the existing regulatory regime that governs human activities in this huge area of the planet. And the big news in this treaty is the ability to fully and highly protect very large areas of the high seas and that is really the key The other companion piece, strengthening management outside of protected areas is also important because the ocean is a fluid environment, obviously. And if you trash the area outside of marine park, the the marine park won’t be as effective as it could be. So the twin objectives of the agreement establishing these marine parks and improving management outside of them really go hand in hand. And those are, in my view, the two most important parts of this treaty.

Hannah Stitfall:

And Lisa, how does the 30 by 30 vision fit into the oceans treaty?

Lisa Speer:

Great question. Countries around the world, in December of 2022, agreed to a global target of protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030. And if you do the math, you can’t get to 30% of the global ocean, unless you enjoy it unless you start protecting large areas on the high seas. And that’s because the high seas are such a big part of the ocean, globally, they’re two thirds of the ocean. So you can’t really get to 30 by 30, without taking action on the high seas. So that’s our goal is to protect large areas of the high seas, we’d like to get to 30%. But we have to do that if we have any hope to achieve the goal that we set for ourselves back in 2022.

Hannah Stitfall:

I mean, how do you even go about starting something like that? You know, do you sit down with the colleagues and be like, Look, we’ve really got to try and get this underway? And then ring up everybody being like, come on, I mean, how do you even go about starting it?

Lisa Speer:

So we have a small group, relatively small group of fellow activists from around the world. And we came together back in the early 2000s, to to really decide how we could what was the biggest thing we could do to help the ocean, not sort of tinkering around the edges, but something really transformative. And we collectively decided, we need a new international agreement that is really focused only on our principally on conservation of the ocean, not on you know, kind of who gets to fish where or how shipping lanes are determined, but really a conservation focused treaty for this international part of the ocean. And so we started talking to individual countries. And we did that both in capitals around the world, but also at the UN, because each country has representatives of its own country at the UN. So these people get together with various meetings and gatherings. So we spent a lot of time in the UN, in the basement of the UN in particular, working in talking with delegates to encourage them to support the launching of negotiations for the for the treaty, and it took about five or six years, but we actually got there, they launched the negotiations, and then from there on, it was really advocacy in all different ways in workshops, and publications and information sessions, helping delegates from different countries kind of understand why it’s important to conserve the high seas, because most people have no idea that there is this area of the ocean that is so vast, it’s two thirds of the world’s ocean, it covers nearly half the surface of the planet. And it is a huge conservation opportunity on a global scale. And that it people just aren’t aware. And so a lot of it was just simple education.

Hannah Stitfall:

And it’s a long time to be working on something, isn’t it? You know, like you said earlier 2006. To, to now it’s it’s a long time.

Lisa Speer:

And well, you know, big things take time. If it was low hanging fruit, it would have been done by now. And so, you know, again, we we really wanted to do something that was not, you know, kind of rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, but that could really achieve transformative change in the ocean. And so we’re not done yet. There’s a lot ahead. But I think that the fact that we were able to reach or that the countries were able to reach agreement last March on the text of the treaty is just it’s a phenomenal and a huge achievement that, you know, the world should be very proud. And another thing I just was very struck by when we when the the agreement finally was achieved. was the extent to which it was a confirmation that multilateralism can actually deliver solutions to some of the planet’s greatest problems. You know, we’ve we’ve seen multilateralism falter in many different areas of society recently. But this was a real confirmation that, in fact, if countries come together, and they are determined to do you know, something good, they actually can get over the finish line. So yeah.

Hannah Stitfall:

And that does bring me on to my next question, because, you know, it was the end of last year 2023, the Oceans Treaty, aka the High Seas Treaty, or the BB and J, was finally signed at the UN in New York. So take me and our listeners there. I mean, what was it like being in that room when it was finally agreed on? I mean, who was there? What was it Like? Did you get on the tables and start screaming? I mean, what what happened? What was the atmosphere like?

Lisa Speer:

Well, so each of the negotiating sessions is two weeks long. And there were typically Yes, exactly. And there were typically two of those year, although during COVID, that that was a pause. So this was the final scheduled negotiating session. And so we all came in, you know, on day one, saying we we’re going to get this thing over the finish line, just imagine a huge room with rings of seats that are occupied by different representatives of different countries. So you have, you know, the UK and the EU, and, you know, all the countries that were involved in the negotiation. They’re all sitting around kind of a half circle, with the President and of the negotiations in the front. And those of us in the non government community, the activists, the green pieces, the NRDC is of the world are sitting back in the kind of nosebleed bleachers, but in the same room. And we, on the last day of the negotiations got to about 6pm. And the President announced that we were going to lose translation at 9pm. And that meant that countries whose principal language is not English, would not be able to participate as effectively. So we thought, okay, we’re going to be done at nine, thank God. Maybe we’ll just run out and get get some food during this little break. Because after a certain point, you’re not allowed back into the UN after like, eight o’clock at night. So we ran out, got food came back. And the negotiators had were huddling in a corner of the basement of the United Nations. And we were not part of those negotiations, we because those were kind of the nitty gritty final details that we’re getting not together. So we were kind of stuck in the UN we couldn’t leave because we couldn’t get back in. And so nine o’clock came and went, the President said, Okay, we’ll be done at 12 o’clock, Midnight. Midnight, and midnight came and went. So people just started to kind of camp out on the floor of the this. This room that is a kind of a conference room. And so people are strewn all over the floor, it looked like a shooter scene. You know, just because everyone was so exhausted. And we were all waiting for this small group of negotiators to come to agreement. Midnight came in, went 3am came in went, still six men went. And finally, and probably I can’t remember the exact time but I think it was sometime in the afternoon of the Saturday, the negotiators came in and had finally reached a deal. And the room erupted into applause, screaming crying, everyone was just it was such an emotional moment. And so many of us had worked for so many years to get this thing done. And when it was actually done. It was just quite quiet at the moment and the president of the negotiation got up and sat in her chair at the front of the room and started burst into tears. It was very up but in the meantime, this is sort of a silly note, but after having been up for 36 hours, all of us look like terrible. You know, we look like something that cat dragged in. And in the meantime, it turns out that it was Model UN day on Saturday. So all these kids are coming in from high schools all over the country and they’ve got little The impacts around their neck. So I represent India and I represent, you know, and they were, you know, kind of get an education of how the UN works. You know, I think it’s so glamorous. And so you know, and here we all are. Anyway, it was, it was quite a funny moment, because I think they got a sense of what what it’s really like it’s not terribly glamorous, sleeping on the floor and eating potato chips for 36 hours.

Hannah Stitfall:

But it was agreed, I don’t think there are many people that can say they’ve slept on the floor of the UN, or are there this is a whole world you’re introducing me and my listeners to that we don’t know anything about I had no idea that that happened.

Lisa Speer:

I don’t think it happens often. This was a really unusual situation. And, you know, I have I have some photos, actually, of the UK delegation, kind of draped over various chairs and lying on the floor with their feet up. And it was really an unusual situation. But it was quite dramatic at the end there. So yeah.

Hannah Stitfall:

And how realistic do you think the vision is to protect 30% of the oceans by 2030?

Lisa Speer:

I think we can do it. I think this is a very ambitious goal. It’s going to take a lot of work and a lot of commitment by everyday people, people like me, governments, politicians, companies, we’re going to need to buckle down and really try to get there. But I think the health of the ocean depends on our ability to protect it. And scientists have been very clear that in order to begin restoring ocean health and resilience and biodiversity, we really need to fully and highly protect at least 30% of the ocean from from damaging activities like overfishing, or damaging fishing activities, like bottom trawling, oil and gas development, shipping, you know, all of the things that that are really posing major threats. And, of course, these are all taking place in the context of climate change, which is having dramatic effects on on ocean life all around the world. And, you know, again, scientists tell us, the best way to make sure that the ocean can remain healthy and resilient in the face of climate change, is to give it a break from some of the other pressures that we put on it and give these areas establish these parks in the ocean, if you will, where wildlife is free to do whatever it does, without human pollution and other activities that are harmful to marine life.

Hannah Stitfall:

So who’s actually enforcing it? And what’s stopping countries? Just bypassing it? So the there?

Lisa Speer:

That’s a very good question. And enforcement in this part of the ocean has always been a very big challenge, because it’s so far away. And we know so little about the ocean, we have such limited capacity to really understand what’s going on out there. So I don’t know if you remember, there was an airliner that disappeared in the ocean, you know, it just disappeared. And nobody’s found it the years decades later. There’s just this profound lack of observation capability that we have. So enforcement is a challenge. But there are really interesting new developments, with satellites and particular satellite monitoring systems that can pick up what vessels are doing where they are. And so that I think the the technology around satellite monitoring is accelerating rapidly. And already, we have a pretty good sense of many of the activities that are going on. So establishing these kinds of parks in the ocean will require us to really have a good solid monitoring system. So we know that, for example, bottom trawlers aren’t going into a protected area, or we’re not seeing any drilling going on in a protected area that I think is really going to be kind of the future of monitoring and enforcement in the high seas.

Hannah Stitfall:

So what are the next steps on the treaty? Because I know it’s been agreed yet, but countries still actually need to sign up for it and then what happens now?

Lisa Speer:

So you’re exactly right. Countries need to sign up for it and in un speak, they need to ratify the agreement which, by ratifying the agreement, they formally agree to be bound by the treaty provisions. And so the treaty needs 60 countries to ratify in order to come what they call come into force, which means become effective. So we need to get to 60 ratifications as quickly as possible, we now have for so we have a long way to go. But our goal is to get to 60 ratifications and entry into force of the treaty by June of 2025. So, it’s an ambitious goal, but just recently, the European Parliament voted to ratify the treaty, which means there there are lots of other steps that have to happen, but that the member states of the European Union will begin to start depositing their their instruments of ratification and we certainly hope the UK will follow swiftly because the UK it’s unclear.

Hannah Stitfall:

If we don’t I’ll pop down Downing Street, and I’ll tell them, I’ll have a word with them, please like we do we need to sign this. Will you go girl? What exactly is stopping countries from ratifying it.

Lisa Speer:

So there are as many different reasons as there are countries, but most of it is, it’s a not a smooth or easy process. Many countries, including the UK, need to adopt implementing legislation by their Congress. So in your your government, in the UK will need to have the appropriate legislative authority to actually undertake the obligations that the treaty imposes on the UK. So for example, there are provisions related to environmental impact assessment on the high seas, that that’s where you have to assess the effects of a potential new activity and report on what you find from the assessment. And countries will need to have their own legal architecture that allows them to actually do that. So it’s a time consuming process in many instances.

Hannah Stitfall:

So the treaty has been agreed on, but each country then has to off their own backs. Make up not make up sorry, but yeah, make up new legislation in order to be able to enforce it. Is that right?

Lisa Speer:

Yeah, that’s right. And some countries that requires legislative action, which means it takes a long time, whereas other countries can do this administratively. So in that, that means they can do it much more quickly. But so the the goal is to get to 60. And there is a big ocean conference coming up. You should come in June of 2025. In June of 2025, it’s in France, and President McCrone has said publicly he wants to get to 60 ratifications announced that at the ocean conference in June 2025 in Nice. So that’s what we’re aiming for. We’re going to be working like crazy to get that to happen.

Hannah Stitfall:

Well, Lisa, thank you so much. It has been a joy to talk to you, you have thank you for all of your hard work for, you know, nearly 20 years working on this oceans treaty. Thank you for spending 36 hours in the UN, waiting for it to come through. I think you’re brilliant. Thank you so so much. And I hope that it will get sorted by 2025.

Lisa Speer:

Yeah, well, come to the companies and we’ll celebrate together. And thank you so much for this opportunity. It’s really lovely to chat with you.

Hannah Stitfall:

Thank you so much.

Hannah Stitfall:

Throughout this series, there’s one question I thought about lots, who are the humans who live and work with the oceans? What does their future look like? And now after that chat with Lisa, I want to know whether oceans treaty fits into all of this. Last week, we met Sharma who told us about her home country of Mauritius, and now we’re meeting a man called Uncle Sol. Uncle Sol is a prominent voice for the rights of Pacific Islanders, including his home nation of Hawaii. And today he’s joining me from a studio in Hamburg. Hello, Welcome, Uncle Sol!

Uncle Sol:

Aloha!

Hannah Stitfall:

Aloha. How are you?

Uncle Sol:

Good. I’m bringing some of the warmth and greeting some Hawaii to your nice autumn. Autumn or almost spring weather?

Hannah Stitfall:

Yes, yeah. I mean, it’s not the best time of year to be visiting Europe. You should have come in a few months time.

Uncle Sol:

I don’t mind the cold. But by the way, I enjoyed it. Yeah.

Hannah Stitfall:

I like it. I like it just that before Christmas, I like it when it’s cold them. But then after that I’m like, bring on spring, I want springtime. So anyway, what are you doing in Hamburg?

Uncle Sol:

You know, I was invited by the the new institute, which is up house and based here in Hamburg. And it was an interesting invitation because invitation was talking about the International Seabed Authority, the ISA, of which I’ve been spending part of my time at as an indigenous Hawaiian. And this, this body that comes out of the United Nations is given the responsibility to manage the area of the high seas, and to come up with rules and regulations for his management. But in the recent meetings that I’ve attended over the last year, it’s become clear that the body is seeking now to consider permitting licences to do commercial mining of the Pacific, which is my home. So this meeting was asking about whether or not it would be possible to think about the ISA, in re envisioning it and repurposing it to become an entity that might consider how to manage and to sustain the ocean, rather than looking at the ocean as a place of a resource extraction. And so that intrigued me and I decided to accept the invitation to come here and speak from my own cultural perspective, amongst others, that are scientists of the ocean and legal attorneys and people who are very well versed in international law. And so that brings me now to Hamburg.

Hannah Stitfall:

Now, of course, I mean, the ocean is hugely culturally important to the people of Hawaii. Can you tell me a bit more about that what the oceans mean to the people of Hawaii?

Uncle Sol:

Well, if you look at the area ocean, we’re talking about the Pacific, you have to know that we have a story that says that we belong here. But you have to also consider that. This is the largest ocean on Earth that has been traversed by voyaging canoes, vodkas. And that these vessels were important in connecting every group of islands, the largest area of islands on earth, by this vessel. And then in the process of using that vessel, you have to consider that these connections were done with intimate understanding of the ocean itself. So we knew the resources of an ocean, we knew the currents of an ocean, we knew the conditions of winds, we knew the cloud patterns, we knew that of animals. And then we found direction using the constants of the stars that was above us, and using the sun and the moon as well. And here is what makes this our home is not just an island in a large ocean, it is an island is connected by a vessel called a vaca. That gives us connection. And we are now intimately involved in the living ocean. And that gives us the ability to be ocean people. So it is now important to recognise that we are not just speaking as Island people from the ocean, but we’re speaking as Island people who have the most knowledge about the ocean. So in the Hawaiian Islands, we have a a genealogy, that is a song that is a chant. And it is one that describes the creation of all things where we live in the great ocean and in the very beginning lines of this genealogy. And maybe I can I can chant it for you if if that’s okay,

Hannah Stitfall:

I would I would love that Uncle Sll place.

Uncle Sol:

And so these beginning lines go like this. No, Kumala Boyka Paul Hey, Connie. Ha ha now Paul ileka Paul here vahini Ha, no coca core, our core is a co op hookah. So those few lines say that, in the deepest part of the ocean of which we live in, there is Mater, Valley volley volley is what is described as the matter. And in the volley volume is this forces of Connie, and wahine. So Kuhmo lipo is the Connie, or the male, and then por la is the vahini, or the female. And this energy in this matter, this organic matter in the deepest part of the sea, they come together, and that energy helps to create the first life. And out of that creation comes the first living creature, which is the COA, or the coral polyp. And then there, after all of the things are created in the vertical column of the deep seas, and then creation takes place in the near shore waters, and then into the lands, and then into the mountains, and then eventually, then even taking flight. And then we are under the beautiful constants of our universe. And so this is the story of our beginning. And so our place here is not to be that of dominance. But to be that of the keepers and the caretakers, it became clear to me that the issues of deep sea mining, that were being considered for, for regulation, and possibly intruding into this space was going to be a disruption and a possible destruction of the place of which I and my life begins that. And I wanted to know if the body had any consideration of that cultural connection to the deep sea. And what I have become to learn by attending this meeting of the International Seabed Authority is that there is no provisions for our relationship to the deep sea. And so it is now important for us now, as indigenous ocean people to come to the body that has given the responsibility and the authority to, to manage the ocean, to consider our perspective. And, and so that, to me, is the importance of of these times. Ultimately, it’s intended to help what we all call climate change. And the questions that we are proposing to ourselves today’s how do we manage to correct climate change? How do we improve on climate change? And I think that the indigenous perspective, and the indigenous experiences and knowledge is necessary to help them.

Hannah Stitfall:

So, talk to me a bit about the Global Oceans Treaty, and how did you feel when that was finally passed last year after decades of negotiations,

Uncle Sol:

I participated in the discussions that preceded the Treaty of the biodiversity beyond national jurisdictions. And at the conclusion of this when the treaty after many, many decades of trying to get to some agreement about the high seas, it became very evident to me that the High Seas is a part of my home. And if it means that we can be part of the solution of finding a way back to balance finding a way back to a sustained ocean, then this treaty is giving us as indigenous people an opportunity to participate. So Hawaii sits adjacent to the area that’s called the Clarion Clipperton area that’s being proposed for mining. Is it possible now to look at this area as part of the treaties intent? I think that even more so this is part of the reason why we need to begin to a Have it that indigenous voice because it is now putting us within the elements of where we have expertise. And I shudder to think about why are we not looking at 100%, you know, of the oceans to be given that kind of consideration, but we’re gonna go with a minimum of 30%. But here, I think is where the conflict I see happening where an agency is seeking now, to do something that goes counter to that kind of idea to one that says, extract, take, destroy. And then the other side of the BB and Jada says, here’s an opportunity to look at care and protection. So we are kind of converging these two very important kinds of things and agencies and governances and laws right in the middle of my home. So I do want to be a participant in the BBN J treaty. And I do want to be able to express our connection to the deep sea at the ISA.

Hannah Stitfall:

And finally, what are your hopes for the future of the oceans?

Uncle Sol:

That the ocean will be given an opportunity to live once more. And then we should learn from that, and know that if we support that kind of opportunity to support our ocean, and all things that are related this, that we should become the beneficiaries of the gifts that the ocean provides for us, which is life itself.

Hannah Stitfall:

Well, thank you, Uncle Sol, for this incredible chat, you have to be one of the most inspiring people I’ve had the pleasure of talking to. Thank you so so much, and keep up the fantastic work.

Uncle Sol:

Mahalo, thank you very much for inviting me. And we have a saying in in Hawaii, eco Guam, Allah. If you want to go forward, eco Guam or Hopi, you need to go backward. And I think a progress for this time is for us to go backward is so that we can move forward.

Hannah Stitfall:

That’s lovely. That’s really really lovely.

Uncle Sol:

Thank you.

Hannah Stitfall:

So where are our oceans headed? Can the relationship we have with nature shift for a future that looks bright. I’ve got one final guest for you. She’s called Marion Osieyo, or Cao. Marion’s worked in the environmental and conservation space for 10 years. And she’s the creator and host of the award winning black earth podcast. It gives me great pleasure to welcome Marian. Hello!

Marion Osieyo:

Hi, Hannah, thank you so much for having me. And, yeah, thank you to your listener community for listening to me.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh, well, thank you so much for being here today. I’m really excited about this. So a lot of the work that you do is how we communicate and think about nature. So talk to me a little bit about that. I mean, how do you see the relationship that we have with nature as it stands?

Marion Osieyo:

As it stands, the data and the evidence shows us that our relationship with nature is really out of balance. The ways in which we treat and take care of nature, collectively, is destroying our beautiful planet at really unthinkable and very devastating rates. But I think every single one of us has an individual relationship with nature. I think that it’s important to also acknowledge that perhaps some of the, you know, for example, in the economy, you know, our global economy treats nature as a resource as a nonliving thing. Yeah, that is for our extraction and for use, but actually, nature is a living being. And nature is a place where we belong to nature is kin nature’s family. So for me, I see humanity as part of nature. And that’s something that’s actually come up quite a lot through my podcasts and the people that I interview.

Hannah Stitfall:

I mean, we are we are we are part of nature, you know.

Marion Osieyo:

I mean, one thing, at least from my own personal journey, as I started to ask this questions about, you know, why is the planet degrading at such a fast rate? Why are so many people unequally impacted by climate change? Where are the solutions, you know, that really challenged me to learn about kind of other cultures and how they have, you know, inherent practices and inherent values in their, in the way they create their societies which invite them to respect and value nature. So I think there’s also an element of like hoping this that, yes, things are really as bad as it can get to be honest. But also, they’re examples that humanity does know how to treat nature with respect and reverence. You know, it’s not a lost cause, that we’re scrambling for solutions. Now, we actually have ideas and inspiration that stem from history that we can also leverage and we can look to as inspiration and motivation that we can do things differently. You know, even if it requires systems change, which is no small feat, but it is possible, it is possible for us.

Hannah Stitfall:

You have your own a very successful podcast, which is all about selling nature, and black women leaders in the environmental movement, and you’ve had some amazing guests on that. And he won best new podcast at the British Podcast Awards last year. Congratulations.

Marion Osieyo:

Thank you. So the silver award, the silver best on your podcast, just to clarify that.

Hannah Stitfall:

Listen, is still very good take.

Marion Osieyo:

I came it. Thank you.

Hannah Stitfall:

And said, tell me a bit about the pod and what have you learned through making it?

Marion Osieyo:

Wow, it’s been a journey. It’s definitely been a journey. I wanted to make a podcast that was inspiring, that was talking about, you know, solutions that work and meeting people who are working on those solutions. And asking them questions about how we can, you know, make these big transformational shifts that we need in our society. And I also wanted to make something that’s authentic. There are so many issues, for example, in the environmental movement that I feel, sometimes we’re not being addressed with enough care issues like inequality, and injustice, but also things like really valuing and appreciating diversity in the way that we take care of Earth, trying to understand how different people around the world have practices from their own cultures, in taking care of the environment. And so I was just really wanting to create a place of celebration. That’s why I say it’s a podcast celebrating nature. And I also wanted to centre the experiences of, of black women and the perspectives of black women. Because, you know, when I thought of, okay, one of the moments in my career that have been so I’ve had a conversation with someone and I’ve just left feeling so hyped up. So excited, so motivated. And there have been genuinely experiences that I’ve had with black women who are working on really groundbreaking, and like radical ideas, you know, that are not just about kind of repairing our relationship with nature, but like, transforming the way we think. And we work and we connect with each other. So I was like, wow, I need to create a podcast, and really bring them and also share with my friends, because a lot of my friends are not in the environmental movement. So sometimes they’re just like, why are you so excited all the time? Like, when I turn on the news, I just see, like, really depressing images of like, you know, animals dying, or like, you know, huge extreme weather, but you just always seem excited. I’m like, Yeah, because I have these amazing conversations that, you know, you may not be have access to, but I can create this platform that allows us to have collective access to this information and insights.

Hannah Stitfall:

Totally, yeah, totally. I’m thinking about the future of conservation. I mean, what would you say needs to shift in attitudes for the for the future to look brighter? Heavy.

Marion Osieyo:

Um, so I think I think conservation is a very exciting discipline. I think stuff like climate overwhelms me sometimes because I’m just like, wow, this this all just seems too scary. It really it really, really does. And I’m just like, okay, but conservation. You get to learn about different species and you It’s just so exciting. I’m like, wow, I get to learn about nature, I get to learn about life, you know how nature creates life, how nature sustains life, and how I can be a part of that. So I think there’s a lot of potential for conservation in the future, I would say that there are things I feel needs to change within conservation. As I mentioned before, different cultures around the world have their own practices of taking care of the earth. And I’d love to see more of that recognised in kind of mainstream or Western conservation science. And that requires working in partnership with communities who live with and around ecosystems. So I think that’s, that’s really exciting, bringing that awareness of, of just the cultural diversity that as a human species we have when it comes to relating with nature, one of the most transformative things that has happened in modern history is European colonialism, in the sense that it changed how we think about nature, like fundamentally. And it’s also really shifted and shaped conservation in some parts of the world. So, you know, things like the invention of national parks and creating spaces, to separate local people from a particular place for the purpose of conserving that ecosystem. But then also on a grander scale, when we think about, you know, patterns of consumption, and production in our economies, those stem from that time, that period in history where we were extracting, you know, resources, extracting energy, extracting human bodies, you know, for the creation of profit, and to gain power over other countries. And it’s shaped conservation is shaped conservation in the UK is shaped conservation around the world. And I think taking time to just understand what are the things that we have inherited from that time in history, into the way we think about nature, and the way we think about other people? And what can we leave behind. So I’m excited to see how kind of decolonizing conservation can really help us think about the planet differently, because we’re at a stage in our society also where, you know, rising inequality, climate change, nature loss, you know, all these things are happening, and, but it’s also a space where we can think boldly about the future where, you know, ideas that seemed wacky or too grand or too idealistic, are actually like, now becoming very realistic options, because we realise we don’t have the time to think small, like now we have time to really think big. Yeah.

Hannah Stitfall:

Well, listen, Marion, thank you so much for coming on today. It’s been a joy to talk to you and for all of our listeners at home, please do go and check out her black earth podcast, obviously, after you’ve listened to this one first. Yes. Do go check it out. Thank you so much, Marion, for being here. Thank you. Yes.

Marion Osieyo:

Thank you so much, Hannah.

Hannah Stitfall:

Here’s Lisa, for a final thought.

Lisa Speer:

I think we’re at a crossroads. We’re at a point where we decide whether we want an ocean that is a dead ocean, that is just merely allows us to keep shipping, but not a whole lot else? Or do we want a vibrant, healthy ocean that provides the world with food, and countless communities around the world with jobs, and the cultural connections that are felt so deeply by communities that live near the ocean that have really great and deep and long ties to the ocean health.

So we are at a point where we can decide what we want. And it’s not always easy. There are many forces aligned against us. But I also think that there is growing recognition of the incredible importance of the ocean to humanity. And I think people are starting to understand that we can’t just kind of assume everything is okay out there. That we need to take affirmative action to begin to protect large swaths of the ocean. So I’m hopeful I feel like the times are changing.

I feel like the fact that this agreement was reached after so many years of effort and is it’s an illustration of the deep concern that is shared by many nations and many people around the world for the health of our ocean.

Hannah Stitfall:

So that is it for now. If you haven’t already, please share the series with your friends and family. And don’t forget, follow us @oceanspod, because we’re continuing the conversation there. And if you want to find out more about what you can do to protect the oceans, there’s a link in the episode description. Thank you so much for joining me. Bye for now.

This episode was brought to you by Greenpeace and Crowd Network. It’s hosted by me, wildlife filmmaker and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall. It is produced by Anastasia Auffenberg, and our executive producer Steve Jones. The music we use is from our partners BMG Production Music. Archive courtesy of Greenpeace. The team at Crowd Network is Catalina Nogueira, Archie Built Cliff, George Sampson and Robert Wallace. The team at Greenpeace is James Hansen, Flora Hevesi, Alex Yallop, Janae Mayer and Alice Lloyd Hunter. Thanks for listening and see you next week. Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Add your name to call on leaders to create new ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet.

Texte intégral (950 mots)

The deep ocean — 200 to over 10.000 meters below the surface — is one of Earth’s last untouched frontiers, but it is under threat from a nascent industry: deep sea mining. Some countries and corporations are racing to extract metals and minerals like cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper from the seabed, pretending that those minerals are needed for a clean energy transition. As if it was not enough to plan to destroy fragile ecosystems, some deep sea mining companies are now marketing deep sea minerals as necessary to strengthen military power, exacerbating geopolitical tensions between world superpowers with worrying implications for global peace and stability.

Deep sea mining: a new arms race?

Until very recently, the industry has attempted to justify its existence on the greenwash argument that deep sea mining is a necessary evil for the energy transition. In other words, they claim destroying the extremely fragile deep sea ecosystem that we barely understand will somehow help win the battle against climate change. But day after day, new scientific evidence suggests that the metals from the seabed are not needed and that the damage could be irreversible.

Twenty-five governments have already either rejected deep sea mining or called for a much more cautious approach, and the industry’s political play is failing. In a high-risk pivot, mining companies are now trying to convince investors and decision makers by telling the world that the minerals from the seafloor are paramount for military purposes. Deep sea mining must be stopped before it starts to prevent further environmental destruction, further stockpiling of weapons and fomenting of conflict.

The deep sea mining industry fanning the flames of the geopolitical crisis to justify its existence?

Companies driving the development of deep sea mining are guilty of greenwashing and hypocrisy. Some of them have been lobbying at the International Seabed Authority, and beyond, to get a greenlight to start deep sea mining commercial operations, especially the Canadian-based frontrunner, The Metals Company (TMC).

TMC seems willing to say whatever it thinks will help it make a profit off plundering the deep sea. One moment, TMC will pretend to care about the planet by pushing the baseless claim that metals mined from the deep sea are essential for the clean energy transition. Then, it’ll be openly supportive of calls to develop deep sea mining in order to strengthen US military capabilities. Minerals, like those found in the seabed, are highly sought out by weapon companies and are increasingly in use for military purposes (for example, in advance weapon systems and laser precision-guided weapons).

In addition to that, the Norwegian company, Kongsberg, a cornerstone investor in the deep sea mining company Loke and strategic partner of The Metals Company, is the world’s leading provider of Remote Weapon Systems. Kongsberg has demonstrated a direct and deep interest in deep sea mining equity, technology research and development.

The race to weaponize the metals and minerals of the deep ocean would have disastrous consequences for people and the planet, fuelling environmental destruction and threatening world peace and stability. The deep ocean must be protected, not exploited, to avoid fuelling wars which will cause untold human suffering. Join us to stop deep sea mining before it starts.

Maud Oyonarte is the global digital lead for the Greenpeace International Stop Deep Sea Mining campaign, employed by Greenpeace France, based in Paris (France).

Texte intégral (1570 mots)

Citizen Climate is an on-going series about global citizens taking action, big and small, for the sake of a healthier planet for us all.

“Imagine a world where we prioritise the well-being of people and our planet, its creatures, and future generations. A world where kindness prevails over judgement, and where understanding replaces prejudice.”

The citizen: Chikumbutso Ngosi is a Feminist Economist activist, an International Project Manager with ActionAid and a founding member of the Feminist MacroEconomic Alliance – Malawi (FEAM). Ngosi is based in Lilongwe, Malawi.

Malawi is grappling with an economic crisis that often heavily impacts women because of traditional, gendered roles. FEAM was born out of a necessity to form a network centred around women’s rights and fiscal justice. Their mission is to influence macroeconomic policies and frameworks, including debt management, to achieve economic justice for women. The Alliance advocates a Feminist Wellbeing approach to the economy, one that prioritises people and the planet over endless growth and profit.

Since 2019, FEAM has empowered over 10,000 young women and women’s rights activists by equipping them with knowledge on macro-economic policies and holding dialogues with key stakeholders to present the lived experiences of the people, while actively working together to closely follow the dealings of the Malawi government with international financial institutions.

My journey into activism and advocacy

My path into activism and advocacy was driven by a profound sense of purpose and a determination to effect positive change. Growing up in an environment where I witnessed rampant forms of abuse against women, I felt compelled to take action.

During my undergraduate studies, I studied education sociology, exploring power dynamics and the pervasive injustices woven into our society. When I started working, I started engaging in grassroots movements and collaborating with like-minded individuals, which fuelled my passion for gender justice and equality.

Over the course of 15 years, my commitment to the cause has deepened, leading me to expand my focus beyond women’s rights alone. I began to explore the intersection of gender justice, climate justice and macro-economics in order to advance women’s rights. This journey ultimately shaped my core area of passion: feminist economics and planetary care advocacy and activism.

Impact of economic growth on women and the climate crisis

The relentless pursuit of economic growth often perpetuates gender inequalities. Women face barriers in accessing education, healthcare, and economic opportunities. In the last 15 years, I’ve seen Malawian women, especially in vulnerable communities, bearing the brunt of climate-related catastrophes. During floods or droughts, they’ve lost home, crops and livelihoods. Their resilience is constantly tested as they are having to rebuild their lives amidst environmental uncertainty.

Economic expansion contributes to resource depletion, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. If we continue prioritising economic growth, we risk climate catastrophe, urging us to rethink our economic priorities and prioritise sustainability over relentless expansion.

UN Tax Convention and a fairer international tax system

The UN Tax Convention represents a significant step towards creating a fairer international tax system for all. Its primary goals are to ensure that developing countries benefit from foreign investment while combating tax evasion.

Key features of the convention include preventing double taxation by establishing clear rules. It aims to prevent situations where income is taxed twice—once in the investor’s home country (residence country) and again in the host country (source country). The convention favours greater taxing rights for the host country, allowing developing nations to expand their revenue base and adequately fund gender-responsive public services.

Civil society as a powerful advocacy tool

Civil society, including women’s movements and young urban women in Malawi, play a crucial role in advocating for change. They serve as a vital bridge between citizens and policymakers. Their advocacy efforts can help shape fiscal policies that are inclusive and responsive to the needs of all, as well as take care of the planet.

In Malawi, through networks like FEAM, women and young activists can actively engage in economic justice advocacy. They are able to challenge unjust fiscal policies, including austerity measures and barriers to women’s economic participation.

Women’s movements within civil society amplify these concerns from a feminist economic perspective. Young urban women lead climate justice movements, demanding their voices be heard in climate policy decisions. This kind of advocacy plays a critical role in promoting sustainable practices and ensuring fiscal and climate policies are gender-responsive. It strengthens advocacy efforts across economic justice, climate action, and gender equality, ensuring that these critical issues remain at the forefront of policy discussions and implementation.

What change would you most like to see in the world?

What I would most like to see in the world is a radical shift toward empathy and compassion. Imagine a world where we prioritise the well-being of people and our planet, its creatures, and future generations. A world where kindness prevails over judgement, and where understanding replaces prejudice.

In this world, we recognise our shared humanity, regardless of borders, beliefs, or backgrounds. It’s a world where love, respect, and cooperation guide our actions, leading to a more harmonious existence for all.

We’re asking governments to put wellbeing at the top of the agenda. Join our global movement and let’s demand wellbeing for all!

Texte intégral (8974 mots)

Everyone knows the oceans are changing. Sea levels are rising, the water’s getting hotter, coral is disappearing. But what does that actually mean? What impact are the changing oceans having on humans? Hannah Stitfall is joined by climate activist Shaama Sandooyea, who explains how climate change is impacting her home nation of Mauritius, and grammy-nominated DJ and environmental toxicologist Jayda G travels to the studio to tell Hannah about her new CNN film, ‘Blue Carbon.’

Presented by wildlife filmmaker, zoologist and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall, Oceans: Life Under Water is podcast from Greenpeace UK all about the oceans and the mind-blowing life within them.

Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music or wherever you get your podcasts.

Below is a transcript from this episode. It has not been fully edited for grammar, punctuation or spelling.

Shaama Sandooyea (Intro):

One of my fondest memories is me standing on the beach in Flic en Flac in Mauritius, which is on the west coast. This is the beach where I used to go with my parents and my family during summer trips.

This is one of my most favourite beaches because of the memories, because of the laughter of the people there because of the scent, the smell of the food, the whole place is just amazing.

But unfortunately, that the change over the past decades because of the beach erosion, so we lost actually a huge amount of beach, small island developing states, we are being affected so much by the climate crisis to the point that the land is being reduced. And yet we are barely contributing to it. So the way that we see climate change in in other countries is very serious as well. But small islands came to a point where it’s disrupting the society there. It’s disrupting the way of life and the way that the people function.

Hannah Stitfall:

This is Oceans: Life Under Water, a podcast series that brings the oceans and the incredible life within them right into your headphones.

I’m Hannah Stitfall. And in this episode: Changing Oceans. We all know that climate change is having a huge impact on our seas. Trawling alone emits as much CO2 as the whole aviation industry. But away from the scary stats, what do the changing oceans actually look like?

Shaama Sandooyea (Intro):

It’s a huge part of us to be from Mauritius. Because wherever you are around the world, and you see Mauritan, the joy that you have. But having that be stripped away is is ripping off our identity of ourselves.

Hannah Stitfall:

Is there any hope?

Jayda (Intro):

Blue carbon essentially is where various plants within an ecosystem they’re really good at pulling carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it into the ground where it stays. We’re basically giving them like a new press release. We’re like, come on guys. This is like the big new, like environmental ecosystem that we should be really paying attention to.

Hannah Stitfall:

This is Oceans: Life Under Water, Episode 11.

I’m really pleased to be joined today by Shaama Sandooyea. Shaama is a marine biologist from Mauritius. She staged the first ever underwater climate protest to highlight the impacts that climate change is having on Mauritius, an island nation in the Indian Ocean, and it gives me great pleasure to welcome into the studio Shaama. Hello!

Shaama Sandooyea:

Hello! How are you?

Hannah Stitfall:

I’m very well! Where are you?

Shaama Sandooyea:

I’m currently in Serbia. I’m not in Mauritius at the moment.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh, I see. Is that where you’re living then?

Shaama Sandooyea:

Yes, at the moment. Yes.

Hannah Stitfall:

A bit different from Mauritius.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Well, it’s not surrounded by the ocean. So yeah, it’s quite different.

Hannah Stitfall:

Tell me where you’re from. I mean, for some of our listeners that might not have ever had the opportunity to go to Mauritius. I mean, I never have, I would love to. Tell us what it’s like. What does it look like? What does it sound like? Tell us a bit about Mauritius.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Okay, so I might be sounding a bit nostalgic, when I’m talking about it because I love my country so much. But basically Mauritius, as all of you probably know is it’s an island. It’s a small island. And it’s found right in the middle of the ocean in the Indian Ocean. And it’s like on the south eastern coast of East Africa, East of Madagascar, and it’s really a dot on the map. But I also like to say that Mauritius is not just a small island, but it’s actually a large ocean state because it has 2.3 million kilometres square of exclusive economic zone which is like maritime zone and everything. Mauritius itself is the main island but we do have smaller islands around like Rodrigues, Agaléga, St Brandon, Chagos and Tromelin. And probably Mauritius is also famous for the dodo.

Mauritius for me, it’s a country that has many facets. So, the first thing that I say when I think about Mauritius is the beauty, the multicultural, the diversity of the people, of the languages, of the way of living. So, there is this part of Mauritius that is abundant with life. You have the endemic plants, you have insects, you have the birds that are flying by the mountains, you have the wetlands. They are sheltering, migrating birds from Europe basically. They are very important for us. We also have mangroves that are protecting the coastline so they are like these trees that are guarding the coast of the island. And of course we have sea grasses, sometimes you can catch a seahorse there. We have the coral reefs. And these coral reefs, they are home to the most diverse ecosystems on the planet, different types of fish of eels, sea turtles, that’s one side of the country that, that I really like to put forward like this, this quality of life, this diversity of life that exists there, the colours, the green forests, the green mountains, and also the blue ocean. And this is just fabulous.

But unfortunately, there is also another side of Mauritius, which is a bit damaged. We have, of course, social issues, a lot of inequalities on the island, but when we focus a bit more about the environment, there is a part of Mauritius that is, that has been pretty much destroyed. I would say since since the colonisation of the island, by the Dutch, British and French, of course, at the time, they were not fully aware of the environment and the importance of protecting it. So a lot of our natural endemic forest has been cleared. And also, of course, the dodo were killed and a lot of animals started disappearing because of that. For example, we had dugongs in the Mauritian waters. But of course, sailors started killing them to feed.

So there is also the side of the island that I really want to have in mind. Because when I speak of about Mauritius, to anyone, everyone is actually very excited about it, Oh Mauritius, it’s perfect! Yeah, yeah, it is beautiful. And I cannot I’m always amazed by the diversity of life, every time I’m seeing a new fish, I’m super excited about it. But also there is this part that is destroyed. And I want to raise awareness on it so that people can understand, Okay, this is beautiful, this is natural, this is paradise, but also we have other issues behind and these issues, they are growing faster than the country can recover faster than the animals can recover. So this is how I would like to describe Mauritius. It has plenty of faces, multifaceted, but beautiful.

Hannah Stitfall:

I mean, it sounds wonderful. Sign me up! Sign me up. I want to go there right now. So for some of our listeners that may not know what a small nation island is, can we can we just expand on what that actually means?

Shaama Sandooyea:

Well, of course! The most common term that is used for that is ‘small island developing state’. So basically, there are many small islands that are developing countries around the world, whether it’s in the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean. You do have like small land territories, if I can say that. But the ocean is, they have a bigger ocean territory, but they’re just like, very small lands.

And they share challenges that are quite similar, whether it’s social, environmental, or economical. Like, for example, on the islands, on the small island developing states, there are limited resources, we don’t have as enough resources as any other bigger country. And that’s a problem because we need to import. Import products, we depend on in our international trade, whether it’s for food, whether it’s for transportation, or for development and everything. So there is that.

There is also the fact that the small islands, they are quite a way far away from from the mainland. So in terms of travelling, transportation, it’s very complicated. For example, when you’re living in Europe, you’re living in the US or Australia or Asia, whichever, like a big continent, you can travel, you can travel and it’s fairly easy. But to get out of Mauritius, for example, you need to have the aeroplane. So it’s always that remoteness that is very challenging. I know for example, a lot of Mauritians that never left the country, and probably never will because it does cost a lot of money. So we have that as well.

And we have the fact that most of these islands they are they are located on subtropical latitude, but the problem is that these places they are more susceptible to natural disasters, like heavy rainfall, cyclones, typhoons, etc. So having these conditions which make them more prone to disasters, and knowing that there are limited resources on the island, it’s complicated for recoveries, complicated for even to be prepared for these things and then to recover.

Also, these islands they they are not just limited in terrestrial resources, but they have a vast maritime resources like like really big maritime zone and a lot of these islands depend on the ocean. Depend on the ocean for food, depend on the ocean for travelling, depend on the ocean for, for just being, as part of their culture as part of who they are. So that’s mostly how I would describe the small island nation.

Hannah Stitfall:

And tell us a bit about what’s happening with the small island nations and climate change.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Okay, so even if all small island developing states, they are facing the same challenges, not all of them are being affected by the same way, by climate change. If we take the example of Vanuatu, if we take the example of some other islands in the Pacific, of course, sea level rise is, is gonna be a huge problem for them, a huge crisis for them because it’s a flat island, so it’s easier for them to be swallowed. But for example, in Mauritius and Reunion Island, we are mostly volcanic islands, and we have mountains we have higher lands. So of course, the sea level rise is going to affect us as well, as it is already – it’s eating a lot of our beaches, but there is still land for us to move to there is still this, there will still be Mauritius, Mauritius will still exist on the map. But it’s just that, of course, when the sea is rising, when the sea level is rising, people are going to be displaced, they’re gonna lose their homes, they’re gonna lose everything. And this displacement is not something that we have enough space for or enough capacity, resources, especially in terms of money. So the challenges are quite complicated.

Also, it depends a lot on… well, we know that every year we have climate phenomenon like El Nino or La Nina. So that also really influences the climate on the islands. In one way you can have, for example, the El Nino we had the El Nino for the summer of 2023 to 2024. And the masquerade islands, Madagascar, we, we witnessed, like an obscene amount of rainfall of water coming from the sky. And it was so serious that the rainy season started way earlier. It started since November. And usually it starts around January, February. It started since November, and almost every week, the government had to close schools because it’s too much water. It’s risky. There were many, many accidents, and you cannot just let people go out when it’s raining that much. And we had some severe cases, not just in Mauritius, but in Reunion Island as well, in Madagascar, where houses are flooded completely people don’t they are pushed out by the water. And they don’t know what to do it was it was very traumatising for the people. Also, at the same time, if we have, for example, La Nina, well, it’s going to be drier condition, which means that we don’t have water.

So even if we do our best to prepare and adapt for it, it’s something that we are limited to adapt to it, we for example, the piece of land that we have is not going to sustain 200 millimetres of water in 24 hours. It’s never going to do that. But also another thing is, of course, when we talk about rain, we talk about drought, we talking about food security. So a lot of a lot of these islands, they have some small plantations, even if they cannot plant like everything. But the extreme climatic conditions make it really hard to grow anything. And even if we managed to do it, where the prices are just going to skyrocket because it’s too… it’s not growing well or it’s bad. So this is these are the main points that I will say about how climate change is affecting small island nations.

Of course, I’m not even mentioning about the social issues that come behind it, but it’s a lot.

Hannah Stitfall:

And just for our listeners at home, El Nino and La Nina are just extreme climatic events.

Shaama Sandooyea:

They are actually natural currents that occur. They are just the different length. El Nino is a different direction and La Nina is a different direction. So these currents they occur in the Pacific Ocean, and they influence the weather a lot in South America, in Australia, east of Asia, and of course Africa as well. For us in the Indian Ocean. If we have El Nino, it means that we’re going to have warm currents and with a lot of humidity and rain, but La Nina for example, in Mauritius, in Africa, of course, it’s small, drier conditions. But if it’s drier for us, then it’s also more typhoons for Southeast Asia. These are like natural currents that exist already. But they influence the climate a lot on the neighbouring countries and with climate change is becoming extreme.

Hannah Stitfall:

And how often is it an El Nino or La Nina year? Is that Is it just every every other year?

Shaama Sandooyea:

No. For example, for the past three years, we’ve actually had La Nina consecutively because yeah, it was a bit problematic for African countries because they had long droughts, but it’s not necessarily one year El Nino and another year La Nina, it can be for example three years La Nina and one year El Nino.

Hannah Stitfall:

Yeah, cuz I was gonna say you know if it, if it is one year one and one year the other then, you know if it was raining raining a lot, then you could sort of, you know, store that water to see us through the next year but you know if La Nina lasting three years. That’s serious drought, isn’t it?

Shaama Sandooyea:

And yeah, it is it is serious drought. And that’s why for the past few years, we’ve seen like horrible drought conditions in African nations like unbelievable, but also now we can see that they are being flooded because of the of the rain and everything.

Hannah Stitfall:

We’ll come back to Shaama in a second because I want to bring back on Richard. Richard’s a maritime lawyer and he was my guest in episode 6, about the Wild West of the High Seas. At one point our conversation turned towards island nations. I’d asked him how rising sea levels were threatening the rights of island nations like Maritius and what maritime law says about protecting them. And I thought his answer was really interesting.

Richard Caddell:

That’s something that’s currently being worked out. Because one of the big problems of the law of the sea is that it was largely written in the 1970s where climate change wasn’t on anybodies serious agenda. I mean, obviously, there were scientist looking at it, but it certainly wasn’t permeating international negotiations in a way that it does now.

Ultimately, when it comes to these small island states, there is a school of thought that says that your boundaries will recede as your countries recede. So if part of your coastal defences start to erode, and those sorts of things, and so your maritime boundaries come back, and the real sting in the tail, is that an island state, for instance, if it is no longer habitable or able to support economic life of its own, then it’s classed as a rock and it loses its maritime entitlements.

So at the moment there is a lot of international litigation ongoing, and there are three separate international courts looking at the issue. But a lot of the small island states are arguing that the maritime boundaries should be fixed at a point before climate change starts to affect them so they don’t lose those entitlements. But of course there is a very real risk that these countries could become eventually, if nothing much is done drastically, could become uninhabitable within the space of, you know, centuries, certainly, two.

Hannah Stitfall:

What do you think? Do you think they should have their boundaries fixed?

Richard Caddell:

I think there is a strong legal argument for that and you can base that on a legal principle of equity, fairness, that those are the boundaries that were fixed in time when we signed this convention, so those are the boundaries that should remain there. But ultimately, that would of course be challenged by more enterprising and more geologically solid states that have been eyeing their resources and seeing an opportunity. Unfortunately human nature is human nature.

Hannah Stitfall:

Ok, back to Shaama…

If Mauritius, as a small island nation, if it were to become unlivable at one point, because of the effects of, of climate change, how would that affect your identity?

Shaama Sandooyea:

I mean, how would you feel about that, and I guess other people from Mauritius, the thing is that we are already feeling it. Because like I mentioned earlier, we had some pretty serious rainfall for the summer 2023/2024. And you don’t recognise your home anymore, you don’t recognise the island anymore. Like it’s destroyed, your house is destroyed. The island where you see is destroyed, the ecosystems are destroyed. And you feel a sense of, of danger, of insecurity, because you’re not sure if you can still be here in the next 10 years. And for sure, if you want to have kids, you’re not even sure they will be able to live here or to sustain themselves here. Like what is the future of the people there? What is the future of the next generations? And, and that’s something very hard because we are I mean, we are Mauritians, we are from an island, we see life differently, but also at the same time, it’s a huge part of us to be from Mauritius. Because wherever you are around the world and you see Mauritians, the joy that you have that someone is from an island is here next to you. It’s amazing! But having that be stripped away is, is ripping off our identity of ourselves. It’s a big thing for us.

Hannah Stitfall:

And are you hopeful for the future of Mauritius?

Shaama Sandooyea:

Ah, well, not so much.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh!

Shaama Sandooyea:

Um, yeah, I’m very sorry about it. I am not hopeful at all because when we look at the picture of how Mauritius is, it’s an island that has been destroyed for the past 400 years probably. And we don’t have enough political will or enough strength to actually make a change. I’m very, I’m criticising always, I’m criticising the government and also the private sector because they are profit driven, they are not driven by the future of the island. Because if they were, they would actually work together with, with the communities there, with the people there, with the workers on the island. But it’s not happening that way is always a system of profit driven. And also at the same time, Mauritius is, I mean, all the states, they are not even contributing to 1% of the climate crisis. It’s not proportionate at all! I mean, whatever we do, even if we start planting a lot of trees on the island, okay, it can help us when we want to, I mean, for example, we want to adapt to the situation of higher heavy rainfall, planting trees and mangroves, it’s actually going to help us to adapt to it and to be stronger to be more resilient. But at the same time, for example, like I mentioned, when we have 200 millimetres of water falling down from the sky, how do we do it? How many trees do we need for it? So there is this part where we are not in control of the climate crisis at all, we are not, we cannot do anything about it for now. I mean, we can advocate for it, we can push, we can pressure the world leaders, we can pressure them, we can push our government, we can pressure the private sector to stop depleting the ocean like that. But I am not hopeful at all about the future of the island. And now we’ve come to a point where they’ve built so many houses on the beach, that they are going on mountains, to build hotels and villas there for wealthy people. I mean, if Mauritians cannot afford housing in the country, why? Why are we doing these things? But that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be hopeless about it. I feel hopeless about it. But that doesn’t mean I should, I should just let it go. Because that’s what that’s what they want us to be hopeless and not do anything and just let them get away with it.

Hannah Stitfall:

Right, so Shaama? We know, things are pretty bad. Yeah. How can we stop it?

Shaama Sandooyea:

Oh, there are so many things that can be done. Okay. So there are things that we all can do by ourselves. Although I believe that it’s not big enough to make a change. I’m very sorry for saying that. I’m trying not to break the morale here. But for example…

Hannah Stitfall:

Give me some hope!

Shaama Sandooyea:

Like switching the way that we consume things, increasing our awareness about it, this is very important. But also, we need to know that every action does not have the same impact at every level. For example, when I’m refusing to eat meat, when I’m refusing to use plastic, okay, it’s going to reduce the amount of CO2 of emitting all the plastic and putting in back in nature and everything. But also at the same time, there is a huge cooperate there still producing plastic and giving to others. So the most consequent actions I can suggest is to take it up to politics, to take it up to the corporates, to the companies that are destroying constantly destroying areas because of the resources because of the oil, the oil industry, keep the pressure on the oil industry keep the pressure on where the government’s on, on world leaders that are refusing to acknowledge the need for climate urgency, because they keep on admitting and they don’t know, but it’s affecting us here in Mauritius, for example. So these are my line of actions that I would highly recommend to people. And I believe that if we keep doing that we they will need to change but yeah, that’s my take on it.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh there you go, for all our listeners at home. That’s our call to action. After you’ve listened to this you’ won’t’ll need to email your MPs get in touch with everybody.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Yeah, and literally everyone, everyone has to be on board with this.

Hannah Stitfall:

Well listen Shaama thank you for coming on today and speaking to me, it’s been it’s been brilliant talking to you actually. Mauritius, I guess, I guess for me, you know, being in England and some of our listeners it seems like a world away and and of course it is one of the frontline places in in climate change. So thank you very much. It’s been really good talking to you. Thank you.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Well, thank you as well. And thank you all, to all the listeners for for paying attention and then doing what’s what needs to be done. Thank you so much.

Hannah Stitfall:

So what can we do? Are we headed for a future where our island nations disappear? I mean, that’s all a bit of doom and gloom, isn’t it? But I’ve got someone else in the studio with me now, who says the answer to that is No.

Jayda G is a Grammy nominated DJ and music producer from Canada, as she also happens to be an environmental toxicologist. Her film Blue Carbon comes out on CNN later this year. And it gives me great pleasure to welcome Jayda to the studio! How are you?

Jayda:

Hi! So glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

Hannah Stitfall:

Thank you for coming on. I mean, I’ve been working in wildlife stuff for a while now. What is an environmental toxicologist? What is that?!

Jayda:

I know, it’s so funny, it’s like on like, my description on Instagram. And like I was talking about it on like, some Instagram real and someone was just like, Yo, what is actually an environmental toxicologist? Like, that’s a great question.